Picturesque downtown Dawson, where you can stop for lunch at Sourdough Joe's. Credit: Tourism Yukon

Dawson City Music Festival, held each year in July, boasts three glorious days of music at a variety of venues. Credit: Tourism Yukon

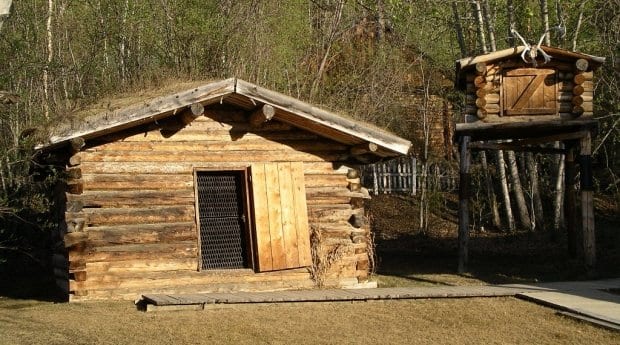

Jack London Cabin and Interpretive Centre at the Dawson City Museum. Credit: Timkal

Aerial view of Dawson. Credit: Dawsonesque

Jack London’s Rendezvous: Heinold's First and Last Chance, is a “last chance” saloon located in Jack London Square, Oakland, California, where London once lived. Credit: Calibas

Diamond Tooth Gerties Gambling Hall is billed as Canada’s first casino. Credit: Timkal

Gambling the night away. Credit: Tourism Yukon

Dance hall girls at the Palace Grand Theatre. Credit: Tourism Yukon

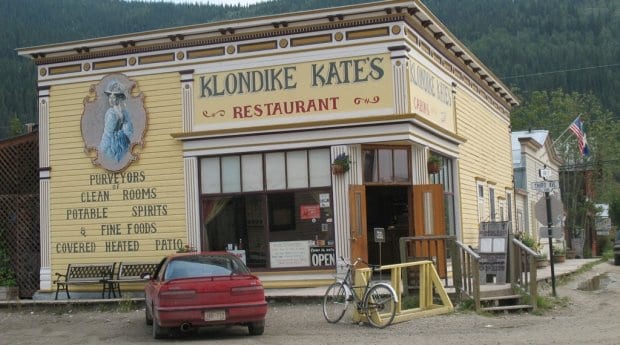

Klondike Kate's Restaurant and Cabins in Dawson. Credit: Hans-Jürgen Hübner

Not your ordinary shop, check out the Dawson Trading Post. Credit: Tourism Yukon

Built in 1922 in Whitehorse, the steam-powered sternwheeler SS Keno is a national historic site. Credit: Tourism Yukon

Walking tour outside the Westminster Hotel. Credit: Tourism Yukon

I’m in Canada’s Yukon territory on a quest.

A quest that takes me from the capital city of Whitehorse to the past and continuing gold-rush town of Dawson City. My excuse is the Dawson City Music Festival, three glorious days of music, beer and goat curry in the town immortalized by poet Robert Service, novelist Jack London and historian Pierre Berton. I’m in the True North Strong and Non-Conforming — a land where people’s quirks and charms are celebrated today as they always were.

My quest is to decode Jack London, whose writing I’ve enjoyed since childhood. He’s best known for The Call of the Wild and White Fang, often viewed as children’s animal stories and widely taught in the American school system. The Call of the Wild follows a kidnapped, abused dog who discovers who he really is and loves and rescues his kindly last owner before joining a wild wolf pack. Set mainly in the Yukon (now known simply as Yukon), it is a very adult quest story, an allegorical fable, of man’s search for self-discovery and his yearning for freedom, friendship, love, happiness and reciprocated duty.

London came north from his Oakland, California, home in 1897 to Yukon as one of thousands in the Gold Rush, spent time in what is now Dawson City and lived with mining partners in various cabins about 100 kilometres upstream on a small river where they had staked a claim.

Just 21, he spent his spare time in Dawson bars letting others buy him drinks. Not yet published, he told his drinking buddies and others he met to remember his name because one day he would be a famous author. He was an avid listener, encouraging those he met to share their stories, and he drew on his nine months in Yukon for the rest of his writing life. On medical advice and with his former mining-claim partners dead, he fled home via a job on a boat.

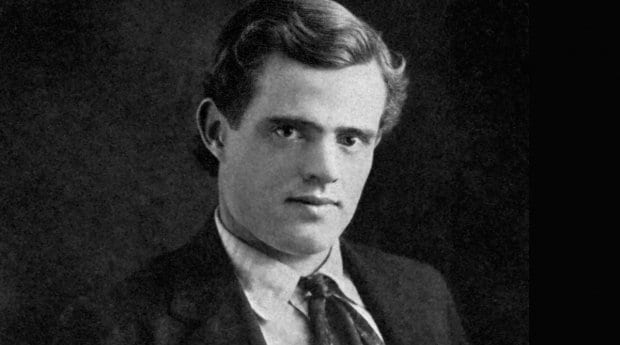

Photos show London as a shortish man-boy, cute in a James Dean way. In fact, Dean and Marlon Brandon copied London’s sensitive-stud-in-a-leather-jacket look. You can check out the photos at the Dawson City Museum dedicated to the writer. The museum’s star attraction is a rebuilt miner’s cabin made partly from logs believed to be from a cabin in which London lived briefly while he and his partners panned their stake. A second reconstructed cabin is in Jack London Square in his Oakland hometown.

I hover outside the door. The cabin seems so small. Romantic, too, with its tiny wood stove for heat and cooking and raised beds, all very rough-hewn wood from floor to ceiling. Romantic, that is, 116 years later in the middle of Yukon’s short summer. In the depths of the eternal nights of the winter of 1897/98, life would have been bitterly cold, and it’s easy to imagine the fights triggered by cabin fever and booze.

Nearby is a separate building housing photos, writings, historical documents and books that document what is known of London’s time in Yukon and some of the rest of his life. It’s staffed by interpreter Dawne Mitchell, who charms some 2,500 visitors who pay homage annually from all over the world, from the United States to Slovenia, Japan to Germany.

“The record was one day last year,” Mitchell says. “There were people from 11 different countries here.”

I ask Mitchell about the less-discussed aspects of London. Was he gay? What do we make of his racism, which he repeatedly addressed, a racism that should shame a boy raised by a black nanny after his unwed mother abandoned him. And how about his life-long revolutionary socialism?

Mitchell has little to say about London’s sexual orientation. But in a talk to a handful of German tourists, she speaks of London’s childhood poverty, the deep depression of the 1890s and London’s having to take on menial, sometimes degrading, work starting at age 14.

Mitchell says London’s racism should be put in the context of his time. Still, he has certainly been punished posthumously for his bigotry: an outcry over naming a Whitehorse street Jack London Boulevard in 1996 caused the city to return to the previous name: Two-Mile Hill. But a conspicuous bronze statue of his face smiles at passersby on Main Street at Fourth Avenue, and a life-size statue graces Jack London Square on the Oakland waterfront.

A web search finds London’s name on lists of historical gay figures. But it’s not that simple. Sure, his writings have a strong homosocial aspect, examples of homoeroticism pepper his novels and short stories, and he repeatedly celebrates strong women characters. But is there evidence of same-sex pleasures?

We know that as an 18-year-old nicknamed “Sailor Jack” riding back and forth across Canada by train, he had an obsession with another tramp he’d heard about named “Skysail Jack.” The multiple trans-Canada efforts became mutual after the other Jack heard about London’s interest. Bad luck prevented a hookup. In 1907 London writes, “We’d have made a precious pair, I am sure, if we’d ever got together.”

We also know that young London was cute, that he shared cabins with other men and was very close to a man named George Sterling, whom he called “Greek” and who called London “Wolf” in return. We know that there were few women in Dawson at the time and that Yukon winters are long and brutal. London also spent time as a sailor, was jailed for his socialist activism, and rode the rails as a “tramp” to research his acclaimed book The Road.

London writes about how an older tramp — a “profesh” — would often take a younger “punk” under his wing possessively. The road-kid or punk then “is known possessively as a ‘prushun,’” London writes. Peter Boag, a professor of western US history, clarifies that punks and prushuns were the “younger male in sexual relationships on the road.”

London writes, “I was never a prushun, for I did not take kindly to possession. I was first a road-kid and then a profesh . . . the profesh are the aristocracy of The Road. They are the lords and masters, the aggressive men, the primordial noblemen, the blond beasts so beloved of Nietzsche.”

Does that mean he was a top only?

But “gay” as a sexual and cultural category did not exist at that time. In the working-class culture of London’s youth, men’s sexual labels were based on masculinity and sexual position. An effeminate “fairy” was considered abnormal. But having sex with another masculine male, especially if he was a top, might have enabled London to view himself as “sexually normal,” as he describes himself in a letter.

London’s second marriage was to Charmian Kittredge, a lean woman whom he referred to as “mate-woman” and “twin brother.” In a 1902 letter, he confides to Kittredge his longing for a “great Man-Comrade” with whom he “might merge and become one for love and life . . . This man should be so much one with me that we could never misunderstand. He should love the flesh, as he should the spirit, honoring and loving each and giving each its due.” At the time, he was back four years from the north and a year away from becoming a household name with The Call of the Wild.

I didn’t find positive proof on my Dawson City pilgrimage that Jack London was into man sex. The photographs of him hanging in the museum tweaked my gaydar, and the historical documents and his own writings tease. The quest added muscle and blood, booze and puke to my understanding of this charmingly provocative character now sadly celebrated for writing about dogs.

He was so much more complex than that.

For more informmation visit dawsoncity.ca.

Plan your trip to the Jack London Centre in Dawson City: travelyukon.com.

37th Annual Dawson City Music Festival

July 24–26, 2015

Minto Park

Dawson, Yukon

dcmf.com

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra