Maurice Tomlinson had to flee Jamaica on a weekend.

Tomlinson, a long-time gay activist now based in Kingston, Ontario, was born and raised in the island nation and married his now-husband in Canada in 2011. He was back living in Jamaica on a Friday in 2012 when the Jamaica Observer published photos of Tomlinson’s wedding on its front page, with the headline: “Jamaican gay activist marries man in Canada.”

Death threats against Tomlinson began to roll in, and he knew he had to get out of the country—fast. By Sunday, the British High Commission had sent Tomlinson a passport on an emergency basis, and he immediately moved to Canada with his partner, a former LGBTQ2S+ liaison for the Toronto Police.

Tomlinson has been living in Canada ever since, but that hasn’t stopped him from fighting Jamaica’s colonial-era, constitutionally sanctioned homophobia from afar. In Jamaica, gay sex is punishable by hard labour and up to 10 years in prison. That law was put in place in 1864 and has been reaffirmed by Jamaica’s government and legal system multiple times in the century-and-a-half since. (That includes a 2012 update that adds those convicted to a sex offender registry.)

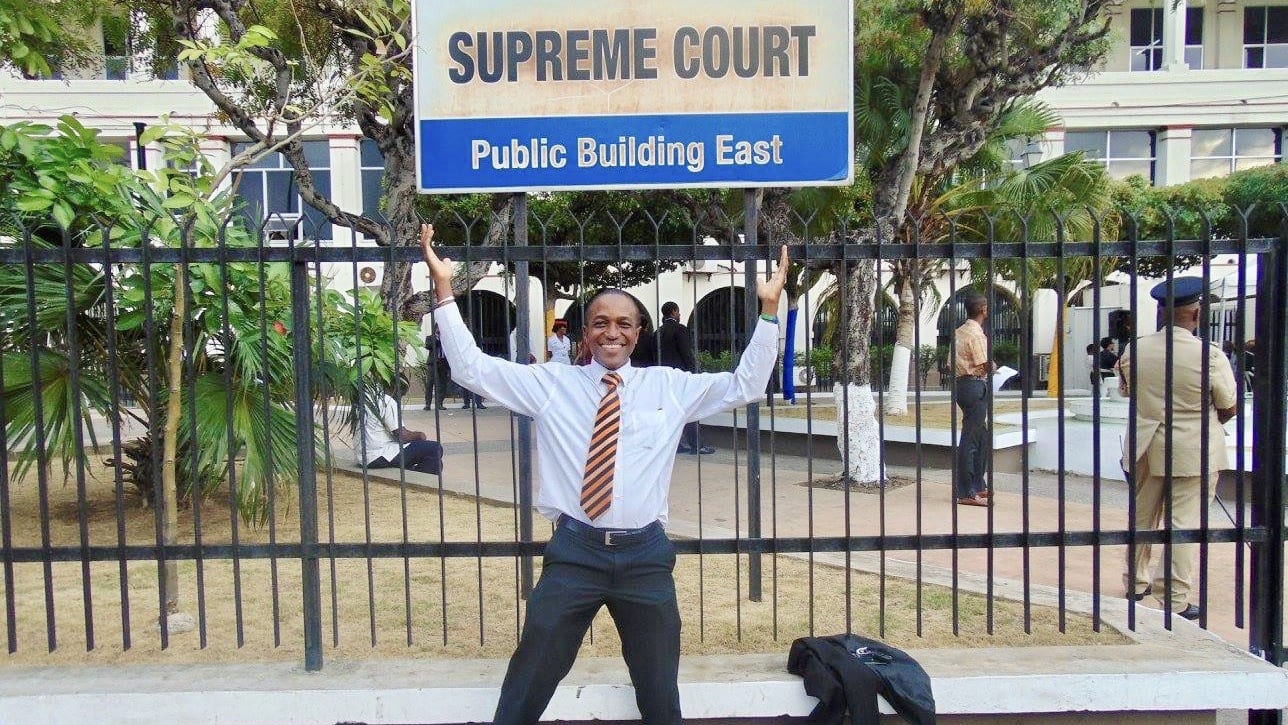

In 2015, Tomlinson filed a case with the Jamaican Supreme Court to overturn the anti-sodomy law. The court refused to allow any complainants to join Tomlinson, but allowed nine anti-LGBTQ+ religious groups to join the suit against him. Now, after nearly six years, the first official hearing for the trial is scheduled to begin on Mar. 8. Tomlinson and his lawyers will be fighting to end one of the most brutal anti-LGBTQ+ laws on the planet.

“Overturning the anti-sodomy law would only be the beginning of a long, hard fight to eradicate anti-LGBTQ+ sentiment in Jamaica.”

Tomlinson faces an uphill battle. Virulent homophobia and transphobia, he says, penetrate every facet of Jamaican culture—from the government to the police to the arts—and queer people are not safe in the country whatsoever. Overturning the anti-sodomy law would only be the beginning of a long, hard fight to eradicate anti-LGBTQ+ sentiment in Jamaica.

But Tomlinson has been overcoming uphill battles his whole life. Born and raised in Montego Bay, he fell into Jamaica’s dominant evangelical Christian faith at a young age. At the time, Tomlinson had long known he was gay but feared that he would either have to hide who he was forever or face a difficult, dangerous life as a gay man in Jamaica.

“I had a very lonely childhood,” Tomlinson says. He bought into the church to get by, and became heavily involved in “homophobic tropes” in an attempt to survive. “I thought that if I was in church, nobody would suspect my secret,” he says. “I felt that I needed to do this to exorcise demons because that was what I was told, that it was demonic.”

Tomlinson graduated from law school in 2005 and started working in an AIDS hospice. He witnessed the link between the LGBTQ+ community and the illness, and that experience sparked an interest in LGBTQ+ rights activism. At 30 years old, Tomlinson married a woman, his best friend from university. They had a son together but he eventually couldn’t maintain the ruse any longer and they divorced. “It was devastating,” he says. “I felt like I disappointed everybody.”

As Tomlinson began to discover himself, he started to shift from working as a lawyer to fighting for human rights in Jamaica—specifically for the rights of queer and trans folks. He spent time educating queer and trans Jamaicans about their rights in an effort to mitigate the abuse they received from police, landlords and the government. He wrote letters to Jamaican media outlets in favour of queer rights.

Credit: Courtesy Maurice Tomlinson

But this didn’t go unnoticed. He received numerous death threats. When he reported these threats to the police, an officer said that he “hates gays and we make him sick.” When Tomlinson reported the officer, his complaint was met with shrugs and dismissal.

“That’s when it dawned on me just how much I was despised in my country despite all my trappings of being a lawyer,” he says, adding that queer folks with privilege experience a different level of discrimination from poorer and more marginalized queer Jamaicans. “The only thing that saved me from being treated in the way some of the other people are being treated was that I had money.”

But that privilege did not save him from needing to flee when the Observer outed him. It was a difficult choice—Jamaica has always been Tomlinson’s home—but he had to leave for his safety. While Canada has provided a place where Tomlinson is free from most of the horrifying homophobia he faced at home, it has bolstered his desire to secure rights for queer and trans Jamaicans.

Tomlinson is using the fact that he is not in Jamaica to draw attention away from queer people on the island and direct it toward himself. It’s partially why he’s the sole claimant in the challenge against Jamaica’s anti-sodomy laws; he is at a lesser risk of physical danger from proudly challenging the deeply rooted systemic norms in Jamaica.

“I feel I must use my privilege to help in whatever way I can,” he says. “That’s what my mother taught me. She’s always looked out for the underdog. So this is how I am.”

He found that his parents were more accepting than he expected. His father has been organizing Montego Bay Pride for the last five years, and his mother has been one of his “staunchest supporters.” But his parents are growing older, and his mother is ailing. Tomlinson wants to go home to take care of her—he’s studying nursing in Canada so he is, in part, better suited to provide care—but right now, it wouldn’t be safe to do so.

Credit: Courtesy Maurice Tomlinson

“I just want to go back home,” he says. “But I can’t go back without my family, and I can’t go back and be a criminal and I can’t go back and have to worry about my job security and my protection in the hospital.”

The Supreme Court hearing could be a start to that long and difficult process. Although the odds seem to be stacked against him, Tomlinson is determined to fight not just for himself but for the many queer and trans Jamaican. If the Jamaican Supreme Court rules against him, Tomlinson will take his case to the United Kingdom’s Privy Council, which is technically the highest legal body in Jamaica. He’s hoping that an external legal force like the Privy Council will rule to end the anti-sodomy law.

“I may not be successful, but hopefully it will lead to some change down the road,” says Tomlinson, adding that once this case is over he will likely pass the torch to other queer and trans activists. “The law needs to go, and I can leave the other things for other people to do. But this one thing I can do, and I feel I must do.”

Correction: March 8, 2021 5:25 pmThis story has been updated to correct the year in which Maurice Tomlinson graduated from law school.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra