“All of my writing,” Leslie Feinberg says in hir measured speechmaker’s voice, “is an extension of my activism.”

Ah, I think. That explains it.

I’ve just finished reading Feinberg’s new novel, Drag King Dreams, and I’m talking to ze in hopes of finding out what’s behind this book-why it reads less like a novel than a 200-page political chain e-mail in all caps, or an interminable speech at a well-meaning but deathly boring rally. (Feinberg, by the way, identifies as female but prefers the gender-neutral pronouns ze and hir.)

The latest book from the celebrated author of the novel Stone Butch Blues (1993) and the non-fiction Transgender Warriors (1996) and Trans Liberation (1998) not only has serious flaws as a work of fiction, but also puts forward a dated and simplistic political perspective.

Drag King Dreams takes us through a few months in the life of Max Rabinowitz and her group of friends. Max works as a bouncer at a bar with a group of other queers, but spends most of her time alone in her apartment, writing Yiddish poetry on the walls.

She was a political activist years ago but has dropped out of politics, particularly since 9/11. There are hints of past trauma remarkably similar to that of Jess, the narrator of Stone Butch Blues: never fitting in, being beaten up as a child and assaulted by police and various men as an adult.

At the end of the book, Max is suddenly re-energized by protests against the war in Iraq and it seems that she will return to activism.

Max’s gender/sexuality is unclear throughout the book. Feinberg says that catching hir characters’ identity takes a “careful reading”-in fact it just requires making it through to the last few pages of the book, where, among other last-minute reveals, we learn that Max identifies as a butch lesbian and another character is FTM.

In spite of a number of careful readings, I was left confused about basic points, like the characters’ motivations, identities and development.

Feinberg insists that both hir novels are purely fictional: Stone Butch Blues is not autobiographical in spite of the fact that its protagonist’s life mirrors Feinberg’s, and the characters in Drag King Dreams are not vehicles for political messages in spite of the book’s activist goals.

“If I have too heavy a hand as an author, my advance readers say, ‘This is you, this is not that character.’ I have to let them take shape in my mind, think about their trajectory, and then let them take that path,” ze says.

But Drag King Dreams is nothing if not heavy handed, especially in the treatment of characters who are queer, of colour or disabled.

It’s reminiscent of the idealized aboriginal characters in Stone Butch Blues who were the only adults to accept young Jess’s gender ambiguity. Jasmine is a quiet yet strong Chinese transsexual woman; Ruby is a volatile black drag queen (or transsexual woman?) who says “y’all” or “child” in almost every line; Deacon is a gentle, organ-playing black man; Heshie is a Jewish disabled computer genius.

The names and character traits scream stereotype.

Echoing one of Feinberg’s main activist messages-the oppressed need to work together to fight the enemy-none of the white queer characters is ever racist. And, outside of this circle of queers, only white people are queer-phobic.

The Chinese medicine doctor treats Ruby respectfully when no one else will. A friendly South Asian man on the street stops to tell Max that she is “on a journey.” And Max’s kind-hearted Muslim neighbours don’t bat an eye at the gender ambiguity that draws death threats from white men.

Why are the people of colour so flawless? I ask Feinberg. Maybe ze intends to counter the anti-Muslim racism of post-9/11? No, Feinberg claims that hir depiction of the Muslim men is based on lived experience.

“The respect and kindness that I experience from Egyptian, Palestinian and other Arab men in the neighbourhood is very real and very tangible.” Neither Feinberg nor any of hir genderqueer white friends has ever “been attacked or even treated harshly by anyone from these communities,” ze adds.

Not only is this quite a sweeping generalization, but this is a novel, right? “It happens in real life” just doesn’t cut it as an explanation. And good characters versus evil characters doesn’t make for successful fiction; they just leave the reader bored by the predictability: we know that the good characters will be victimized by the evil ones (cops, yuppies, landlords) and yet they will stick together and fight with dignity.

Again I end up confused-on the one hand Drag King Dreams is purely made up; on the other the stereotyped characters are based on reality. On the one hand the book is an extension of Feinberg’s activism; on the other ze leaves the characters to their own devices.

Max lives in “the house arrest that the world has sentenced [her] to.” Whenever she leaves the apartment she is in danger: cops follow her, teenagers throw food at her, a hospital security guard threatens to kill her.

Max has short hair and is sometimes called “sir.” But the level of threats and violence directed at her is shocking, particularly since she lives in a queer community sometime after 2001 and spends most of her time in New York City.

When I tell Feinberg how surprised I am by Max’s experience, Feinberg says that ze, too, is the object of hostility every time ze leaves hir home. “People call me ‘sir’ and they call me ‘ma’am,’ but I’m never passing. What people see when they see me is always gender queerness. When people are yelling, ‘Go get him,’ they’re assigning the ‘he’ to me, but it’s not because I’m passing, it’s because I’m being pursued.”

Feinberg goes on to assure me that no one who looks at ze ever sees “straight white gender-appropriate male.”

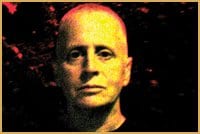

How could I question this claim? And yet, people I know who have seen Feinberg in person say that ze passes as male-and these are genderqueer folk who know that Feinberg identifies as female. Ze certainly passes to my eyes in photographs.

And how can ze possibly state with certainty that ze never ever passes? This would involve reading the mind of every person ze encounters. Am I missing something as a non-genderqueer femme?

I did a quick survey of urban trans, butch and genderqueer people I know, and though they do sometimes experience hostility, they do not live in the level of danger that Feinberg describes.

Do I chalk up the extremes of Drag King Dreams to Canadian/American differences? Or could I suggest that Feinberg has a worldview that is unrealistically black and white and maybe even a little paranoid?

By the end of the interview, I am as frustrated with Feinberg as I am with hir novel.

Feinberg has worked so hard-and successfully-for trans rights. Ze travels from coast to coast giving speeches and readings to packed houses and is so beloved that internet searches turn up just two tiny critical notes among thousands of ecstatic praises.

And yet ze tells me that ze can never make eye contact on the street for fear of violence.

Both the author and the novel seem trapped in a world in which identity is based on oppression and suffering and the lines between good and evil are clearly drawn. It’s neither fertile ground for inspiring politics nor for satisfying fiction.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra