Cianan, Kinnon and Chris getting cheeky. Credit: Jamo Best

Revellers relax on the beach after the conclusion of Doing It, a gay conference held in 1982, organized by the Toronto Gay Community Council. Credit: The canadian Lesbian & Gay Archives

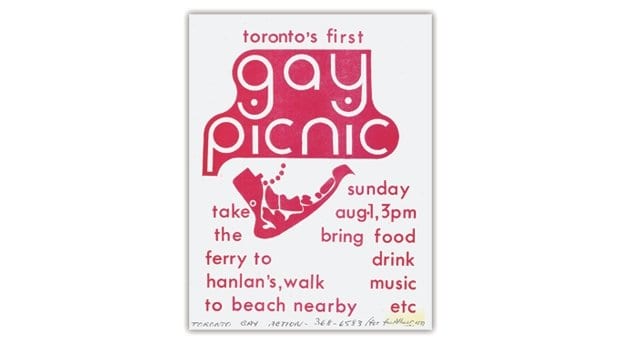

A flyer for the first Pride event in Toronto — a gay picnic at Hanlan’s Point, in 1971. Credit: The canadian Lesbian & Gay Archives

On a sunny Sunday in mid-July, it’s hard to believe that Hanlan’s Point was ever anything other than the sandy oasis many Torontonians have grown to love. Perched atop the dunes at the south end of the beach and looking north toward the city, I watch as nude sunbathers wade in and out of the water and groups of friends gather on blankets to gossip, chat and sneak swigs from hidden bottles of alcohol.

Behind me, the leaves rustle as strangers sneak past on the sandy trails, eyeing each other tentatively before pairing off and disappearing deeper into the brush. The air buzzes with possibility. In a city famous for prudishness and good behaviour, the beach feels like a place where anything can happen, and it often does.

Birth of the islands

Like much of Toronto, the Point has always been in a state of flux. Before a severe storm cleaved it from the city in 1852, the islands were actually a sand spit that extended out from the mainland just west of present-day Ward’s Island. The earliest records available suggest that the local native populations used it as a place of recreation and farming before the Crown purchased the land and established a military outpost there under Lieutenant-Governor John Simcoe. Invading American troops destroyed the fort in the War of 1812, and the area soon gave way to private residences established by local citizens looking to escape the crowded mainland.

Still, it was hotelier John Hanlan who made the most significant impact on the area. After another major storm destroyed his family’s cottage on the Point, Hanlan opened a hotel in the mid-1860s to take advantage of the area’s growing popularity as a vacation spot. Ownership of the islands also transferred to the city around this time, and so improvements were made to the area surrounding the hotel to make it more attractive to visitors, with the addition of parks, a boardwalk system and gardens.

Hanlan’s son Ned, a world-famous sculler, brought additional attention and revenue to the resort, and soon more hotels and various attractions began to populate the area, including a shooting gallery, carousel, dance hall and an open-air theatre that brought in vaudeville acts. An official amusement park featuring a number of popular roller coasters opened in 1895, followed by a stadium built for the local minor league baseball team, the Toronto Maple Leafs.

Taking it off

It was also around this time that local naturist groups lobbied successfully to make Hanlan’s Point a clothing-optional beach, an attractive choice for many of the visiting Europeans who were used to bathing in the nude back home. The area gained a bit of a salty reputation as a result of the bylaw, and attendance numbers went up.

With much of the Western world entranced by theme parks and various other industrial advances of the time, Toronto was leading the pack with outdoor entertainment facilities on par with those found on New York City’s Coney Island or in Blackpool, England. In fact, many of the same ride promoters and performers travelled between the parks and advertised as such in their materials.

The Point continued to be a popular destination for both locals and tourists until a series of events led to a decline in attendance. One such event was the opening of Sunnyside Park in the early 1920s, followed a few years later by the creation of a mainland baseball stadium. As Torontonians embraced the automobile, trips across the lake became a less attractive proposition. Moreover, motion pictures had replaced vaudeville as the leading and more affordable form of popular entertainment during the Depression era, leaving many of the island’s live performances seeming dated in comparison.

Concerned citizens’ groups, put off by the public nudity on the beach, were successful in getting the permit repealed in 1930. By the time the city razed a large portion of the theme park to make way for the island airport in 1939, the area had fallen largely into decline.

A new park emerges

Few paid much attention to Hanlan’s Point for most of the first half of the 20th century. The Metro Parks Commission took control of the islands in the mid-1950s, and the area was cleaned up and promoted as a day-use recreational space, with the installation of park benches and picnic tables. Eventually, a marina was built and the Centreville theme park was created, although it was only a sliver of what the Hanlan’s theme park had been at its height.

Hanlan’s Point took on a queer identity of sorts during this period. The beach continued to have a reputation as an “unofficial” clothing-optional space despite possible fines, and this attracted many young gay people interested in getting some sun and cruising in the dunes that isolated the beach from the city. In fact, the first-ever Pride event — a gay picnic on the island — was held there in 1971.

In 1999, nudist groups, with the help of then-councillor Kyle Rae, were successful in getting the beach reinstated as a clothing-optional space, and attendance numbers steadily increased. What had been unofficial and under the radar for several decades became more commonplace, and advances in gay rights made the beach attractive to a larger swath of Torontonians.

Behind me, the leaves rustle once again, and a man appears. He smiles for a brief moment, then disappears back into the darkness. I glance back over the beach, at the laughing faces as the sound of tinny pop music floats in over the waves. Although the specifics may have changed, the general atmosphere has remained consistent — a space of amusement and recreation.

I rise and disappear into the brush behind me.

How to get there

Normal travel time by ferry to and from the Toronto Islands is about 15 minutes in each direction. The ferry service is fully accessible for wheelchairs.

Directions

The Toronto Ferry Docks is located at the foot of Bay Street at Queens Quay, just west of the Westin Harbour Castle hotel.

Toronto Island Ferry information

416-392-8193

toronto.ca

(Search for “Toronto Islands”)

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra