I’m not going to tell you how Indian director Hansal Mehta’s new film Aligarh ends — you’re far better watching it yourself — but it’s unexpected, unsettling, and raises more questions than it answers.

The title cards after the last shot, explaining what followed the events of the film, will send you scrambling for Wikipedia to find out if it really happened. So here’s your one (sort of) spoiler: It actually did, mostly.

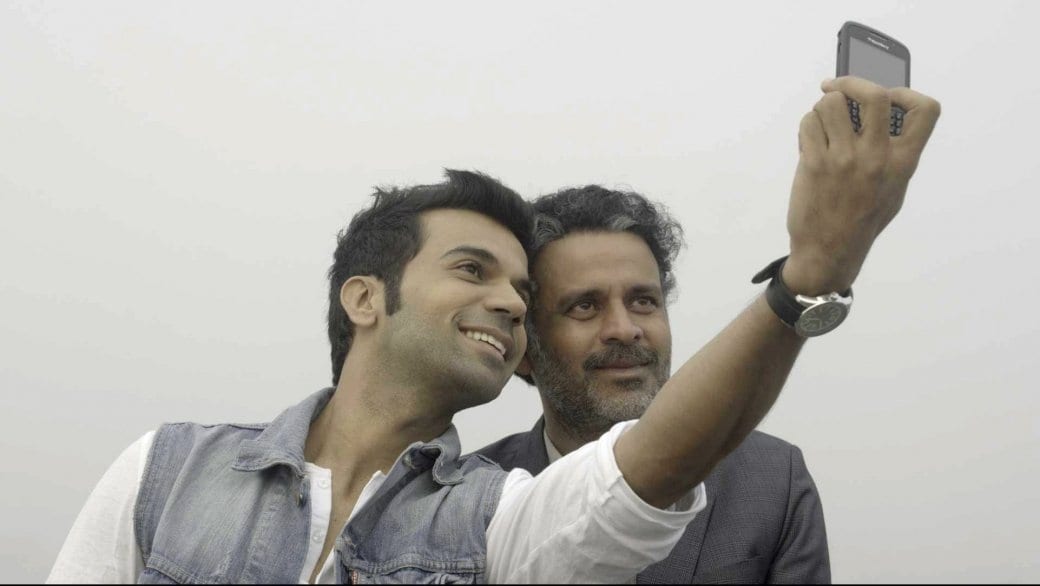

Shrinivas Siras (played by Manoj Bajpayee), a professor of languages at a Muslim university in the north of India really was kicked from his job after the crew of a local TV station broke into his home to film him having sex with a rickshaw driver. He really was dragged reluctantly into the heart of the national legal fight for LGBT rights, and his story was really brought to light by the work of young Times of India reporter Deepu Sebastian Edmond (Rajkummar Rao), though their close friendship in the film is mostly fictional.

Most importantly, the mysteries that surround the end of the film are just as unresolved in real life.

The most fascinating part of Aligarh’s true-to-life style is that we can immediately dive into the facts behind the film and weigh the evidence directly. You can watch the real Shrinivas Siras give a television interview during the events of the film, and read Edmond’s actual reporting on the story, as well as his reflection on his own motivations for the actions portrayed in the film (beware: serious spoilers, obviously).

If anything, Aligarh is weakest when it departs from reality — for example with an odd and unnecessary romantic subplot, and unrealistically dramatic court arguments.

The film is also rooted in India’s legal history surrounding homosexuality, one of the strangest in the world. In 2009, the Delhi High Court found unconstitutional India’s colonial-era law banning sexual behaviour “against the order of nature,” sparking a renaissance of gay public figures coming out of the closet.

In 2013, however, India’s Supreme Court reversed the lower court decision, forcing India’s gay community back into the closet.

Since then, legal and legislative attempts to decriminalize homosexuality, including a high-profile petition by gay Indian celebrities this year, have all failed. This legal flip-flop has made India one of the only countries in recent history to take a major step forward on gay rights and then an equally major step back.

India also shares the same bitterly ironic historical reversal on homosexuality as many other colonial nations. Ancient Indian culture had plenty of space for homosexuality until the invading British imposed their own moral code and introduced the foreign concept of “sexual offences against the order of nature.” Today, Western-influenced LGBT activists are trying to undo the harm done by Western imperialism a century before.

This is where we find poor professor Siras, caught between Western LGBT activism and India’s Victorian morality, and in the unstable window between the decriminalization and recriminalization of homosexuality.

The film Siras, like the real Siras, rejects the title of “gay” as a foreign imposition on his identity.

“I don’t understand this word,” he complains to Edmond. “Your generation wants to put a label on everything.

A scholar steeped in India’s poetic tradition, perhaps Siras is the voice of a post-colonial India, demanding a new way of looking at Indian homosexuality, neither in terms of Victorian morality or LGBT liberation, but something uniquely its own.

I asked Fatima Jaffer, the director of Vancouver queer South Asian organization Trikone, about Aligarh. She says Siras’ story can teach us here in Canada about non-Western ways of being queer — especially important in the days of Black Lives Matter.

“I think this film is about how queer is seen in this very narrow way, not just for white queers, but Western queers, including South Asian Western queers,” she says. “And I think this film will be very important for showing us the different ways in which sexuality plays out.”

“It’s very Indian to be queer,” she says.

Aligarh

Tuesday, Aug 16, 2016, 6pm

International Village, 88 W Pender St, Vancouver

queerfilmfestival.ca

Read all our 2016 Vancouver Queer Film Festival coverage:

It Runs in the Family: A Filipino family’s coming out story

How a Beyonce concert in Brazil helped build queer community

Why four Latina lesbians were accused of raping children

Re:Orientations: What does Asian Canadian queer identity look like today?

Chemsex: sensationalist film or useful warning?

In particular, barbara findlay: Meet Vancouver’s pioneering lesbian lawyer

Can a gay man be attracted to a bisexual woman

What happened to the gay dancers who toured with Madonna?

Troublemakers: When young queers tell their elders’ stories

Two Soft Things, Two Hard Things uncovers LGBT Inuit history

And our paid sponsored content, written by the Vancouver Queer Film Festival:

Top picks for queer flicks at Vancouver Queer Film Festival 2016

The steamiest scenes at the 2016 Vancouver Queer Film Festival

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra