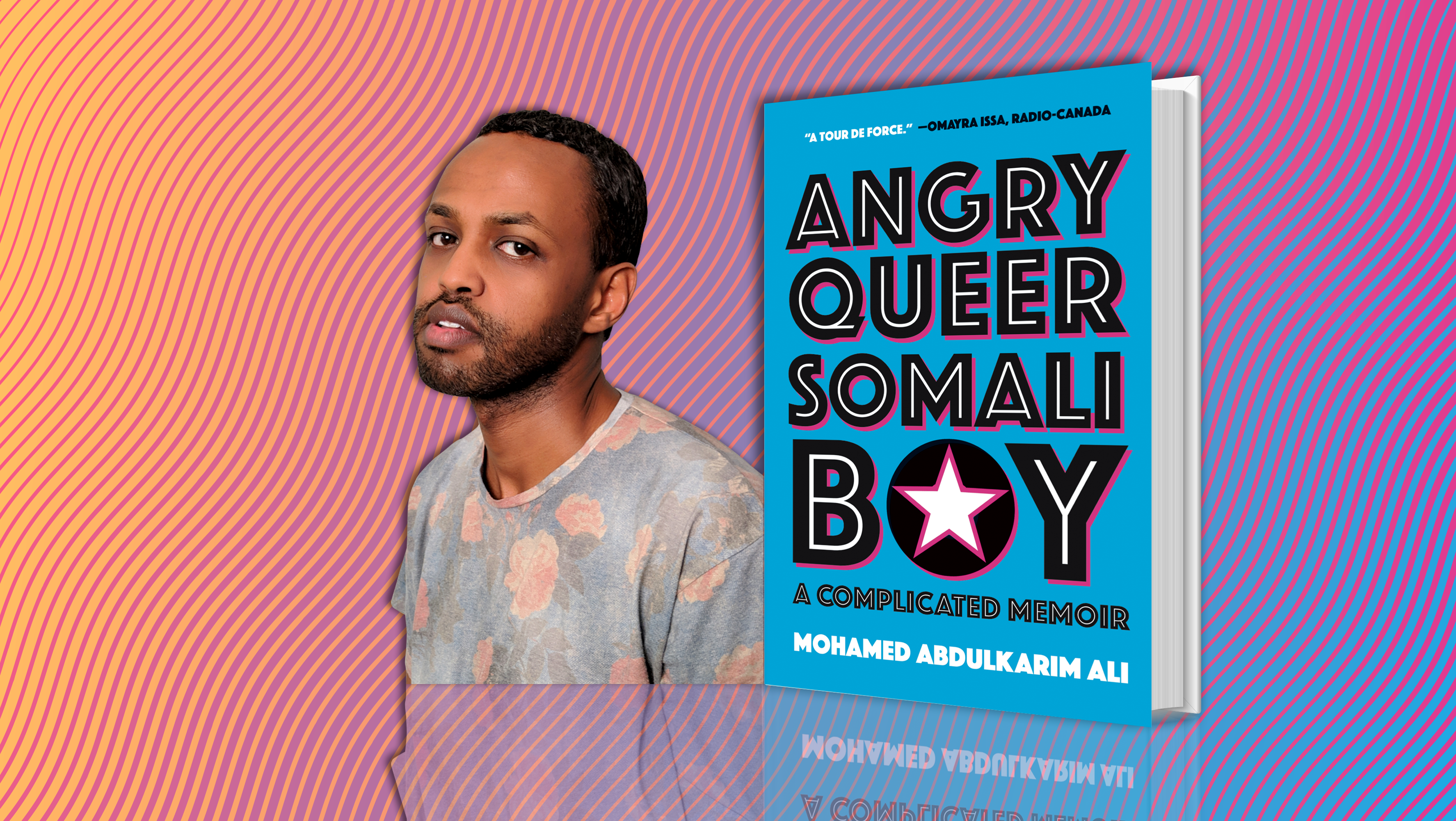

In his debut, coming-of-age memoir, Angry Queer Somail Boy, Toronto-based author Mohamed Abdulkarim Ali recounts his harrowing story of being taken to the Netherlands from Somalia by his stepmother and then later brought to Toronto. Navigating Somali tradition, Western culture, displacement and queerness in the ’90s and early ’00s, Abdulkarim Ali shares his unrelenting account in his memoir, out on Oct 5. This exclusive excerpt picks up on coming into his identity as a queer Somali teenager in the Netherlands, and as a young adult in Toronto.

I coped with a diminished sense of self by diving, headfirst, into the world of drugs. I smoked hashish with hoodlums. By age thirteen, I had moved on to pills.

The chemical name of my pill of choice was diazepam, otherwise known under its brand name: Valium. I was introduced to it by a classmate. On a sunny afternoon, he invited me over to his place. I was in love with him, so I agreed. He had an air of superiority that was intoxicating. He rode a Porsche bike while mine was from a mail-order catalogue.

We rented a townhouse in the vast proletarian hell between the industrial canals and the dairy farms in the south of the Netherlands. His family owned a beautiful townhouse in the centre of town. His life seemed rich and full of love. I could tell that his mother cared about him because his lunches weren’t leftovers or a cheese sandwich.

We made our way upstairs. He turned to me and asked if I’d try something. Here it was, I thought, my first encounter with his body! I had seen him naked in the change rooms and knew exactly where I wanted to place my hands. When he returned from the bathroom with a bottle of pills, I was deflated.

My mom takes these to calm her nerves. Here, have one. Chew them up so they work faster.

I was in heaven. All worry washed away. I laid on the rug and chewed another. I asked him to bring me more the following day. Before I knew it, I was taking them every day.

During my second year at Cobbenhagen collegiate I became friends with Selim. He was the son of Turkish immigrants who ran a furniture shop on the North Ring Road. His hair was jet black and his jeans tight, showing off his bubble butt. I was taken with him as soon as he sat down next to me. He had been held back a year and looked older than the rest of the boys, inspiring fear and commanding respect. He woke me from my Valium-induced naps by stroking my hair.

Selim introduced me to his friend Elson, who had also been held back. Elson’s flirtations were more overt than Selim’s. He sat close and whispered sweet nothings into my ear.

Mohamed, I think you’re sweet.

His lips pressed against my ear.

Do you like me?

His warm breath burned me up. I wanted to grab his face and stick my tongue down his throat, but I was a coward. These boys wanted to do things to me. Elson was a beautiful boy whose parents were from the Antilles. His face betrayed generations of interracial fucking. He exuded a confidence and masculinity I wanted inside of me.

School work and learning the Quran took a backseat to pill popping and craving exotic boys.

My first foray into storytelling was in Grade 10 in north Toronto. It was for an English course taught by a child of Eastern European immigrants. In that story, I referred to the depth of someone’s hair colour as “oily black”, which my teacher corrected to “jet black.”

As part of our final writing assignments, we read a novel and wrote an essay about it. She brought me a title from the choices on the assignment sheet. It was The Power of One by Bryce Courtenay. He was a white South African writer who lived in Australia.

It told of a child raised by a Zulu mammy on a Boer estate. As the boy nursed on the repressed history of his nursemaid, he had vivid dreams, of the automaton kind fashionable among Surrealists. In one of them, the farmer’s child dreamt he was Shaka Zulu.

I didn’t understand the anger I felt then, but I can vocalize it now. It was a poisonous book. The child nourished from the African woman’s body in order to inhabit her history. The child, wealthy and white, is then adorned with the crown of a Black king who died resisting colonial advances. The child is the white future feasting on the trounced Black past of South Africa.

These reflections, rather youthful and incomplete at the time, collided with the blossoming of my sexual nature. Being a bibliophile was a wonderful cover. I read erotic novels and looked at Leni Riefenstahl’s photos of South Sudanese tribesmen. I didn’t grasp how quickly Hitler’s cinematic propagandist had gone from worshipping Aryan zest to documenting African grace. Nothing Riefanstahl produced competed with the Internet. It had hours of pornography of every variety. I sought out porn involving Black booties doing battle with Black dicks.

During these searches I was introduced to the realm of interracial gay sex. Its pervasiveness astounded me. It was a mission to find men like the ones in my environment without the porn involving a white body. The theme was always the same: A poor white queen in distress who had no choice but to give up his shaved booty to throngs of Black dicks. The thugs alluded to in the titles didn’t refer to the white bottom. I knew who the thug was. If we weren’t criminals, we were seducers who excelled, far more than the white producers of the film, in the art of sex.

Europeans didn’t know of sub-Saharan Africa until the Portuguese sailed around the Cape of Good Hope. The imagined dominance of Black bodies, skin, and “blood” was something that can be laid at the doorstep of Greco-Roman colour symbolism. It was rooted in the Greek and Roman association of death, misfortune, and ill-omen with the colour Black.

By imbuing the colour with sinister meaning, they transferred those views onto the African form. Herodotus, during his time in Egypt, wrote about topless dancers on riverboats along the Nile. Liberated dark breasts offended his sense of propriety. In Pliny, the African ceased to be human and morphed into a monster. We were creatures who used oat straws to drink because we had only one orifice in our faces. Those ideas were absorbed into a nascent Christianity and provided us with lovely nuggets of Black mischief. According to the ascetic and hermit Saint Anthony, the devil came to him in the form of little Black boys and girls, eager to defile him. He was setting a trend for the priests of the future Church.

The idea that Black flesh is violable and to be used as one pleased pervaded many Arab lands. Eventually, these ideas found confluence in the home of Christopher Columbus. The Europeans in North America gave these pernicious views about dark skin a whole new meaning. Black Americans converted to Islam because they thought it lacked the racist history of Christianity. In the Americas, Islam may not have been a contributor to the idea of the African as a monster, but if they scratched the surface a little deeper, it became clear that Abrahamic faiths viewed darkness as evil and lightness as the imprint for God’s innocence on Earth.

Away from the prying eyes of my family, I transformed my exterior. Gone were the baggy clothes that drowned my bony frame. I wore tighter jeans, flowing shirts, and coats that weren’t emblazoned with an American sports team.

The call centre I worked at gave us gift cards to the Eaton Centre, the giant mail near Ryerson. I took the $50 and $100 gift cards and headed straight for the sales racks of fancy stores. Not the type of fancy stores that line Toronto’s ritzy Mink Miles, but the upscale versions of the garbage retailers that dotted suburban plazas.

I was determined not to let anything stop my transformation into a visible homosexual. I went so far as to utter that truth to one of my classmates. She was the granddaughter of Italian immigrants from Scarborough, an architectural abyss in the east of Toronto. She was the first person I came out to, but she wasn’t fazed. I wanted her to be elated for me. I craved reassurance, and her indifference, albeit very tolerant, was intolerable to me.

Excerpted from Angry Queer Somali Boy: A Complicated Memoir by Mohamed Abdulkarim Ali © 2019, Mohamed Abdulkarim Ali. All rights reserved. Published by University of Regina Press.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra