I drove from work to my father’s place on a perfect May afternoon. But despite the sunshine and open car windows, I was dreading the encounter since his call the day before.

“There’s something I need to talk to you about,” he said over the phone. My father, Gordon Sr., was a few months shy of 74, and I was nearing my 44th birthday. Still, a summons from him sparked anxiety. It always had, and worsened in the years since my mother died. Did I do something wrong? Did I fail to do something? Was he in financial trouble? Another bout of cancer? Depression?

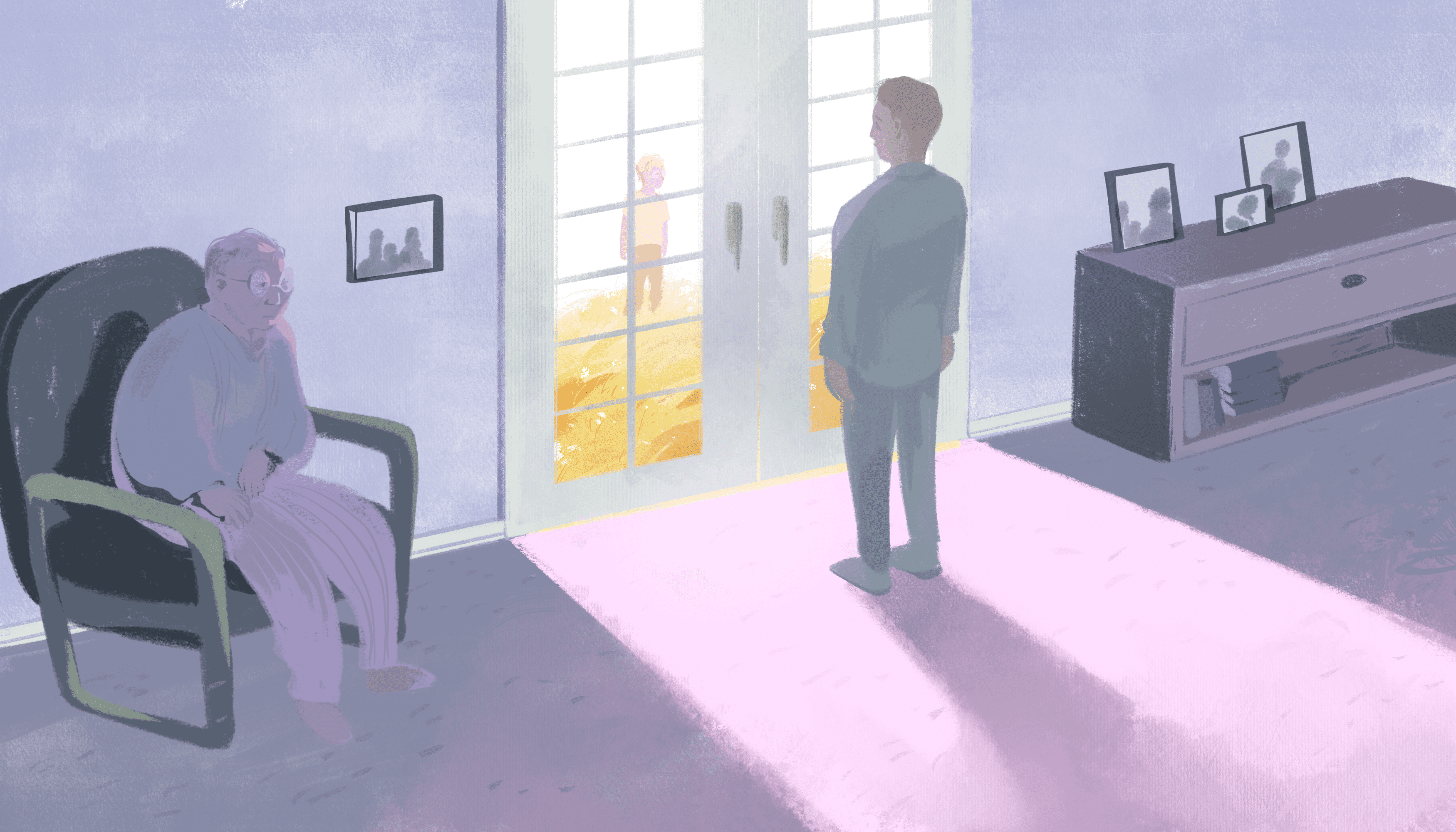

When I arrived, my dad was quiet as he let me in—seating me, unexpectedly, in his favourite chair and positioning himself as far away from me as the living room allowed. He sat stiffly, in profile, barely looking my way.

From the far end of the sofa, he began: “Gordie, I’m gay,” and then added slowly, “I’ve known all my life.”

It seemed like time slowed down. I got up and made my way to him. He was still looking away, tearful, almost embarrassed. I put my arm around his shoulders. His head fell against my chest.

“I thought you had bad news,” I said as I hugged him. “This is really okay, Pop.”

Dad was a slight man, far shorter than I, and quite frail. As I was holding him, he seemed even smaller. We sat that way for several moments, and I kissed the top of his head while he calmed down.

My dad told me he had known he was gay since he was three or four. But growing up on the prairies during the Great Depression and World War II, he never heard anything about queer people—definitely nothing affirming.

Gordon Sr.’s father, Ivar, came to Canada from Norway in the 1920s. He was a railroad man, working most of his career with the Canadian National Railway, where he was a foreman on a work gang. Old photographs of my grandfather show a man with a powerful physique, the result of hard labour and his time amateur boxing. From what I gather, Grandpa was a bit of a brawler and expected his sons to be able to defend themselves. If word got out that Dad lost a schoolyard fight—almost a certainty, he told me—my grandfather would have him fetch the other boy over for a re-match in the yard. Invariably, he would lose again.

At some point later, when dad was a young man, Grandpa regaled him with a tale of gay-bashing. According to my father’s account, Ivar was sitting in a beer hall somewhere out West, when a very drunk man sat down beside him, smiled and placed his hand on his knee. My grandfather’s response was to take the other man out to an alley and beat him senseless.

I’ve wondered over the years if the story was true, or if my grandfather embellished it for an audience that would be impressed by this. Also, I’ve wondered if my grandfather was sending a message to his bookish, shy son: This is what he thought of gay men.

As we sat and talked that afternoon, my dad shared about his marriage. Mom had always known, he said.

My parents got married in 1958. My mother was a nurse and was my father’s caregiver. She had been there for him throughout his many health problems, including several surgeries. I could only imagine her supporting dad as he sought conversion therapies—trying to be straight, hoping to fix himself—from psychiatrists in the ‘60s and ‘70s in Toronto.

“I’ve wondered if my grandfather was sending a message to his bookish, shy son: This is what he thought of gay men.”

In 1998, a week short of her 65th birthday and only months before their 40th wedding anniversary, my mother passed away. A few years after her death, Dad sold their retirement home in Elliot Lake, Ontario, and came back to Toronto with the goal of eventually coming out.

“Who else knew?” I asked.

Dad answered: A couple of close family friends and our family doctor who, I knew, didn’t think highly of psychiatry. I asked if he supported dad’s quest for a cure. He had advised against it, dad said.

My uncle John also knew. Uncle John was not a relation—youngsters of my time didn’t call adult friends of the family by their first name. He had been my father’s oldest friend since the late ‘50s. My mom adored him. When my parents were in university and broke, Uncle John babysat me so they could have a night out. He played the piano and gave me some tips on guitar, and we sang together occasionally. By the time I was in middle school, I pieced together that Uncle John was gay. He died of AIDS-related complications in the late ‘90s.

Although Uncle John was a dear family friend, Dad never spoke of him after he disclosed his HIV status. I’ve often regretted not reaching out to John. He was by no means the only person I knew who was lost to the AIDS epidemic. But looking back, I suppose the fear of HIV/AIDS and the stigma it carried probably played a role in my staying in the closet.

A few days before Dad came out to me, he called his older sister Margaret in Edmonton to tell her. After sharing, my Aunt Marg said, “Gordon that’s wonderful. I’m so happy for you.”

“I was worried you might be upset,” he responded.

“Why should I be upset about a thing like that?” Aunt Marg answered. “At my age?”

Though I didn’t ask, Dad assured me that he had never been “unfaithful” to my mother. I did have questions though: Did he have a support group? Yes, he was in a group for gay fathers and had also joined a social group for gay men.

Did he have a partner? He was looking.

My dad and I talked a little about the homophobic harassment I endured throughout middle school in the early ‘70s as a kid who didn’t fit in with the jock sons of old boys at a private Catholic school in Toronto. He told me he agonized over those years.

During that afternoon in 2004, a little part of me wanted to come out as bisexual to my father. I had known since my early 20s, but I wasn’t ready—and that was his time. I’ve often described the conversation as the first time I felt Dad was completely honest with me in a way that truly mattered.

Growing up, I came to believe that there was a secret in my home—hinted at, but never spoken aloud. Both my parents were heavy drinkers, and when I was 12, my mother told me that one day my father would tell me what she had sacrificed to stay married to him. I now know what she meant by that.

“Growing up, I came to believe that there was a secret in my home—hinted at, but never spoken aloud.”

My father tried to end his life three times that I know of. Once as a young man, again when I was about five years old and recently after my mother died. In that last attempt, I spoke to him on the phone while he was hospitalized. Sobbing, he told me, “All I ever wanted was for my father to love me.”

I now know why he said that.

Fourteen months after that conversation, his friend called me up to let me know that Dad was in the hospital. Cancer had returned, this time attacking his stomach.

By then, I hadn’t seen much of Gordon Sr. Our relationship was still fraught, and despite any progress we might have made, tension remained. I was still in the early years of my sobriety and coping with depression. Dad still drank and could be difficult to deal with at times. Still, he was in hospital and the end was near, so I began to visit him every day.

My father had recently remarried to a nice man named Henry whom he had introduced to me the year before. As Dad’s cancer progressed, his pain meds were increased. He was in and out of consciousness for a few days. Then, one July morning, a nurse called me to let me know that he was near the end. Staff on the palliative care unit were in and out as I sat by his bed until he took his last breath.

I held him as he began to slip away, telling him that everything was okay and kissing the top of his head. It’s unlikely he heard me, but I needed to say it. A few days later, Henry and I sat together at the memorial service.

Both wedding rings Gordon Sr. had worn were placed with his ashes.

I’m absolutely certain my father’s experience propelled me towards coming out myself. Growing up, I saw the damage done by a life lived in secret—but I also understood the fear of rejection and the fear of being seen as a liar.

“I saw the damage done by a life lived in secret—but I also understood the fear of rejection and the fear of being seen as a liar.”

During a very serious bout of depression last year, a mental health professional told me, “It seems like you haven’t really processed coming out yourself.” It was an astute observation. My own coming out was marked by supportive friends and family. I found a new community. I began advising gay-straight alliances as an elementary school teacher. I was many years sober. I thought I had managed well, but I was still prone to cycles of anxiety and dark moods.

I decided to recommit to therapy and found a psychotherapist versed in trauma who worked within queer communities. Sixteen years after that visit with my father, my new therapist said in one of our sessions, “You know, Gordon, you’re still processing what your grandfather did to your father.”

Having lived in a different era from my father, and having lived a life of relative privilege, I had not attended to my own wounds. Memories of my father were painful, and I didn’t want to look too closely. I recall thinking after he passed that he could not hurt me again. There would be no more emails or late night phone calls admonishing me and my wife for not respecting his grief after my mom’s death.

I learned what my therapist called, “Big and little ‘T’ trauma”; it’s the idea that individual experiences that don’t seem significant on their own mount a cumulative assault on the psyche. I reflected on that and on intergenerational trauma as well. I thought, if my grandfather hated what my father was, then he hated what I am, too.

My dad and I never completely mended our relationship. We were men of different generations who shared not only being queer, but not having examined our own lives. Still, the conversation we shared that May afternoon nudged me forward in life. We never bridged the gap between us when he was alive, but that’s okay. His experiences now speak to me. For years, I saw a man that I feared at times and disliked at others. Now, I see a very hurt little boy who never had anybody stick up for him. That’s where I find the connection to my dad, because I was that kid, too.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra