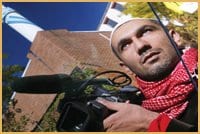

More than five years in the making, spanning 12 countries and nine languages, A Jihad for Love is no small feat. But director Parvez Sharma feels all the hard work was worth it, if only to give a voice to the Muslim world’s most unlikely storytellers: queer people.

Sharma arrived in New York just as the city experienced the 9/11 attacks on the World Trade Center that sent shockwaves throughout the planet that can still be felt today. Sharma’s existence was fraught with duality and he began to experience a wholly different kind of intolerance: it was one thing to be gay in America in 2001, but to be Muslim? That was just asking for trouble.

“No one was speaking about the kind of Islam I knew when I was growing up and I felt that I needed to come out as a Muslim,” Sharma says over the phone from his home in New York. “[The film’s] not just about being gay or lesbian. You are claiming your faith and that was the primary imperative for me —to take some of the discourse about Islam away from the violent fringe.”

For starters, he named the film A Jihad for Love. In the Western world, the word jihad has come to be associated with terrorist attacks and CNN stories, and has fueled a tremendous amount of Christian fundamentalist propaganda. In actuality, Sharma says, the term means a deep, personal struggle, and this struggle for love is what he documents as the film’s subjects struggle to reconcile their sexuality with their religious beliefs.

Sharma acknowledges that homosexuality is not a very visible part of current Islam, but insists that this is a relatively recent development (the last 30-40 years, documented in Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis), and that there is still space for gays in the Muslim world, even if those spaces flout conventional ideals.

“Very often we adopt an arrogant Western perspective towards analyzing life in Muslim countries,” Sharma says. “Islam has a tradition of homosexuality being celebrated in the arts and the culture for hundreds of years. And it has existed even as a part of the mainstream.”

According to Sharma, it’s sometimes even a rite of passage for people to have gay relationships before they enter into marriage. But due to its patriarchal structure, this actually creates a uniquely double-edged sword regarding lesbianism in Muslim society.

“Women’s sexuality is often denied. It’s simply not discussed,” he says. “And sometimes in that realm of invisibility, [lesbianism] can exist in a much more fluid way than male homosexuality, which would be seen as threatening.”

The question of coming out takes on an entirely different scope when committing one’s story to film for the entire world to see.

Sharma spent many years carefully crafting relationships with his subjects, building friendships between people who had often struggled alone, insular in their religious and sexual identity. Though prepared for the obvious obstacles of secretly filming a gay documentary in Muslim countries, Sharma found some unexpected opposition from the gay Muslim community.

“Anytime when a community is repressed and silenced, and when someone steps out of that silence, dares to do something, then people react to that.” Sharma says. “People didn’t want to trust me. But, being a Muslim, I was filming with that Muslim lens; I was very critical of how much of myself I had to give. Many of the really remarkable people in this film were breaking a tremendous silence, sharing what is deeply personal.”

Despite the initial wariness from the community, the film has resonated with audiences of all varieties: queer, straight, Muslim, Christian; even atheists have been fascinated by A Jihad for Love’s intimate examination of faith and sexuality. But the real challenge is getting the film shown in Muslim countries.

“I showed the film in Turkey and the response was amazing, and in my home country, India,” Sharma says. “But I really hope I can take the film to Arab countries one day, that I can show the film in Iran. A few people have been smuggling tapes into Pakistan, for example, where they’ve organized screenings already in the last few months, so I hope efforts like that will continue so that people who really need to see the film are able to.”

This is where A Jihad for Love works on multiple levels: aspects of the movie are meant to lift the veil of silence on homosexuality for Muslims and people in Arab countries, while other parts of the film serve to expand the Western notion of what it really means to be gay and Muslim.

Sharma, for one, is wary of the North American tendency to impose its Western ideals.

“The question really, is who gets to define freedom, and on whose terms?” he says. “Are we going to dictate freedoms based on our concepts of what it means to be gay in the West to more traditional ancient cultures? Or, are we going to allow them to develop their own concepts of sexual freedom? I very much lean towards the latter.”

Ultimately, A Jihad for Love is also meant to reach out to gays who feel an affinity for a higher power, but may have felt the need to sacrifice their religious beliefs when they claimed their sexual identity.

Sharma himself comes from a relatively secular background (he did not attend religious school like many young Muslims) and had already dealt with coming out during his late teens, but says he developed a great respect for Islam through his film’s subjects. He hopes A Jihad for Love will assist other queer people to reconcile their spiritual beliefs.

“I realized through the most trying times these people drew sustenance from Islam and what they believed to be their Islam. And that, for me, was very empowering,” Sharma says.

“I think the film is expanding the consciousness of the audience who is watching it. Not just expanding the understanding of Islam, but faith, which many queer people abandon because they don’t find spaces for themselves within faith.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra