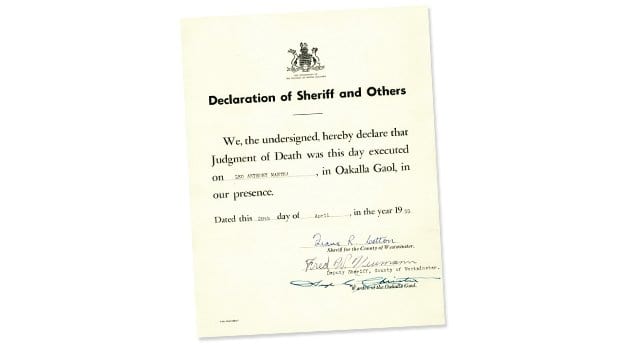

Leo Mantha was hanged at Oakalla Prison Farm in 1959 for the murder of his former lover Aaron (Bud) Jenkins. Credit: Stan Piontek

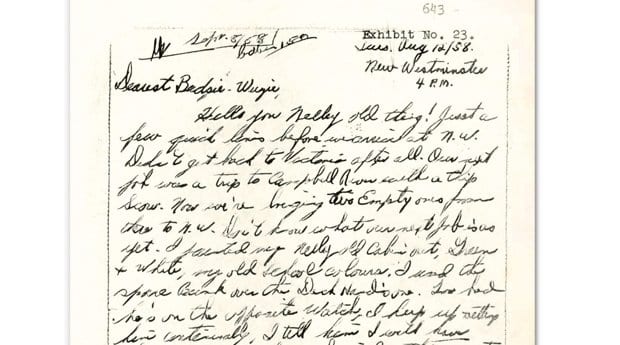

A letter written by Leo Mantha to his lover, Bud Jenkins, in 1958. Credit: Stan Piontek

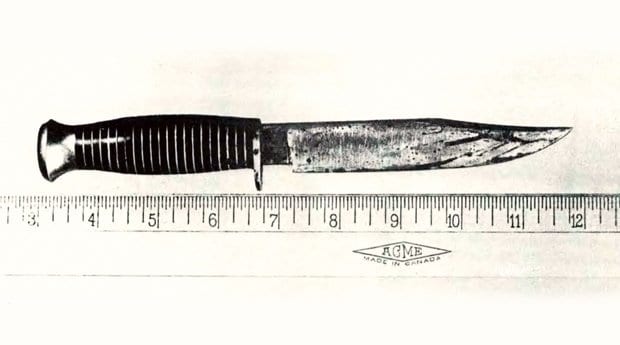

The murder weapon, a 9.1-inch hunting knife. Credit: Stan Piontek

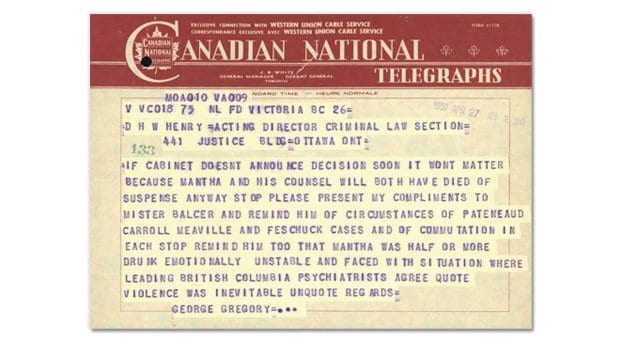

Leo Mantha’s lawyer, George Gregory, asks the federal cabinet to commute his client’s death sentence. Cabinet refused. Credit: Stan Piontek

There’s no doubt that Leo Anthony Mantha was a murderer; he confessed to it prior to his execution 55 years ago in BC.

The question is why was he executed in a time when capital punishment was decidedly on the wane in Canada and most first-degree murder sentences were commuted to life imprisonment? The answer, it seems, has everything to do with homophobia.

Mantha was hanged at Oakalla Prison Farm for the murder of his former lover Aaron (Bud) Jenkins.

“EXECUTED according to the sentence imposed,” reads his death certificate on a line normally reserved for violent deaths. The boxes to indicate whether a death is an accident, suicide or homicide are all unchecked.

Shortly after midnight on April 28, 1959, Mantha, described by one witness as a “stocky, swarthy, toughly handsome man,” shuffled into a dimly lit abandoned elevator shaft that served as the prison gallows. He stood over the trap door in the centre of the rectangular room as the hangman, who had travelled from Montreal for the occasion, strapped Mantha’s legs, then slipped a black hood over his head and a noose around his neck.

The hangman stepped back from his prisoner and pulled a lever on the floor. The trap door gave way.

Mantha dropped “fast and hard,” leaving nothing but a trembling rope and a trace of phlegm in his wake, hanging for 12 minutes before the prison doctor declared him dead.

He was the last man ever executed in British Columbia.

***

‘‘Christ, there’s no way they should have hung him. It was awful,” says Stan Piontek, who knew both Mantha and Jenkins and is now one of the last surviving witnesses from Mantha’s trial.

“It was a crime of passion,” he maintains. “If Bud had been a girl, they would probably have given him a life sentence or sent him to jail — but not hang the person. That was awful what they did.”

Piontek, who now lives in a West End high-rise, served in the Navy from 1952 until 1959. He and Jenkins both worked in the pay office at the Naden naval base in Esquimalt.

Mantha, a marine engineer, first met Jenkins in the spring of 1958. They became acquainted through what Mantha described as a “crowd at Victoria — all homosexuals.”

Piontek says the men got together for drinks at each other’s homes or in pubs, and for sex. “Everybody went their own way,” he recalls. “Some guys would go to Beacon Hill Park and go along the bottom and do some sunbathing down there, but other than that everyone kept to themselves, pretty well.

“Bud and Leo just hung out with each other,” he says. “They didn’t hang out anywhere in particular … Maybe coffee or at a house.”

Mantha had been dating Jenkins for four months at the time of his arrest. He later told an army psychiatrist that he had never been “involved so deeply [affectionately]” with anyone. “No, no one had ever stirred me up like Jenkins, I don’t know why, except that I was loafing and drinking a lot and out every night,” said Mantha, who described his final weeks with Jenkins as a whirlwind of alcohol, sex and “very little sleep.”

Mantha was born in Verdun, Quebec, in 1926. He would later tell a prison psychiatrist that he had his first sexual experience at the age of 16 with an older boy who later became a priest. Raised in a strict Roman Catholic household, Mantha struggled with his sexuality.

His sexual encounters with women were unsatisfactory, and he eventually gave up. He noted that he wasn’t able to sustain an erection with women but would get hard easily — almost too easily — from talking about sex with a man.

He joined the Navy in 1951. Shortly after his discharge in 1956, a military psychiatrist diagnosed him with a “personality disorder with alcohol and sexual deviation” and found him unfit for duty, recommending that he be placed under psychiatric treatment in Montreal.

“He gives a long history of extreme conflict over homosexual tendencies which he recognizes as socially unacceptable and feels very shameful,” the report reads. “So long as he does not drink he can control them, although they still make themselves felt from time to time. Obviously the service is the last place in the world for a man with this sort of conflict.”

By 1958, letters sent by Mantha, who was working up the coast in a tugboat, to Jenkins reveal that he had largely abandoned attempts to suppress his sexual orientation. In one letter he affectionately addressed Jenkins as “Budzie-Wuzie” and “you nelley old thing.”

“Well, darling, I hope you are behaving yourself, also same for Gerry and Don,” he wrote. “Miss you terribly, hope you do likewise. Maybe we’ll be down in Victoria soon, I hope. ’Bye for now, much love and kisses, Leo.”

Mantha’s affection was not reciprocated by Jenkins, who felt that his lover was becoming too possessive.

“I was with Bud when he opened that letter,” Piontek recalls. “He seemed sort of upset because everyone did their own thing and cruised their own way.”

The relationship began to unravel after Mantha returned to Victoria on Aug 5, 1958, and culminated in a fight on Sept 5.

During this period, Mantha shared an apartment with Jenkins’s cousin Don Perry, at 451 Superior St in Victoria’s James Bay neighbourhood.

“I was drinking that day and night — all that day — at the apartment. We drank a bottle of whiskey from 8 to 11 that evening — and beer,” Mantha later told an army psychiatrist. “We watched TV and argued.”

Mantha described Jenkins as a cock tease. “I saw that he was just playing me for a fool and he got me so riled up,” he said. “He had started insulting me — said I was just a sucker, that he was just taking me for everything I had. We used to go out a lot and I would usually foot the bill, well, he was trying to tell me that he was no longer interested in me.”

Jenkins then told Mantha that he wanted to end their relationship and marry a female friend. Mantha punched him, twice.

Jenkins, who was 23 at the time of his death, was described in police documents as a “homosexual (feminine type).” He was the youngest of six children in a staunch Anglican family.

“I met him on the causeway, and he was sobbing and there was some blood on his eye,” Piontek recalls, motioning toward his right eye. Piontek took Jenkins to a cocktail bar in the Empress Hotel, where Perry worked as a waiter. Jenkins told Perry what had happened, and Perry advised him to wash the blood off his face and return to base.

“His uniform was at 451 Superior St, and I went back with him there, and while he was getting changed we were talking, telling me how he was beaten up and everything else,” Piontek says. “It turns out that Mantha had been in the next room to us, and he would have heard everything.”

“Well, I decided over this fight that our friendship had come to an end, which hurt me very much,” Mantha told the court, “and I was just disgusted with what had happened and couldn’t see much in the future, so I was contemplating packing it all in.”

“What did you mean by ‘packing it all in’?” asked defence lawyer and Liberal MLA George Gregory.

“Well, I figured I would drive up the Island Highway over the Malahat and give her the gas and just let her go and I would go over the cliff there.”

On his way to the Island Highway, however, Mantha decided to stop at the Naden naval base in Esquimalt in a desperate attempt to salvage his relationship with Jenkins.

“Well, I was hoping if I saw Bud and could speak to him and try to patch things up, and then I would not have to do what I was going to do,” he later testified.

Mantha sneaked into the barracks and entered Jenkins’s room, where he and his roommate were sleeping. He stabbed Jenkins twice with a 23-centimetre hunting knife.

“I stood beside the bed and Jenkins was laying on his back. I think I bent down or reached down — I was going to ask him — and just at that moment he turned and moved,” Mantha told the court. “I think that startled me and the next thing I recall is his screams and I got panicky and ran out of the place. He started to scream and I ran away and out the same way I came in.”

Jenkins’s roommate was awakened by a loud, high-pitched scream. “Help me, oh God, help me,” cried Jenkins, who was bleeding from his nose and mouth. He staggered toward the door, collapsed in the hallway and died within minutes.

Mantha escaped from Naden without being detected and returned to his apartment. Perry, who had since returned from work, advised Mantha that he couldn’t “keep a friend by being possessive or by beating them.” He then noticed blood on Mantha’s fingernails.

Before they went to bed, Mantha called to Perry and said, “I am in more trouble than you think.”

“What could be more serious than to beat your friend?” Perry replied. Mantha explained that he had followed Jenkins to the base after he left and attacked him once more.

“How could you attack him more seriously than you had already done?” Perry asked.

“I don’t mean I attacked him with my hands. I stabbed him with the weapon.”

“My God, Leo, how could you do that to Bud?”

Mantha was arrested at the apartment and confessed his guilt within five minutes.

***

During the nine-day trial, Mantha’s defence lawyer argued that the murder was a result of uncontrollable passion inflamed by excessive drinking. He told the jury that no man in his right mind would break into a military base and murder a soldier — the chance of success was “absolutely nil.”

He reminded the jury that Mantha was “charged with murder, not with being a homosexual” and suggested that if he was found guilty because “the world would be better off without Mantha,” the same line of thinking would also apply to Jenkins.

Throughout the trial, Mantha’s sexual orientation was described as a problem that exacerbated his “brittle and explosive personality.” Victoria psychiatrist Douglas Alcorn told the court that the passions ignited by rejection on the part of homosexuals were more intense than for heterosexuals.

“The homosexual is under peculiar stresses and peculiar strains which, frankly, manifests itself in outbursts of rage, panic, fear, beyond that which one would normally expect, and in a peculiar fashion in a heterosexual individual,” Alcorn said. “In other words, it has been long recognized that the homosexual is peculiarly prone to such outbursts.”

In his charge to the jury, Justice John Ruttan advised jurors that they were dealing with an abnormal person.

“Certainly I think the accused was provoked, and that is why the fight started,” Ruttan said, “but do you consider a normal person could be provoked in a similar manner?”

After about three hours of deliberations, the all-male jury found Mantha guilty of first-degree murder, which left the judge only one option.

“Leo Anthony Mantha, the sentence of this Court upon you is that you be taken hence to the prison from whence you came and there kept in close confinement until Tuesday, the 19th day of March, next, AD 1959, when you shall be taken to the place of execution where you shall be hanged by the neck until you are dead, and may the Lord have mercy upon your soul,” said Ruttan, who quickly realized March 19 was, in fact, a Thursday. Without apology, he brought Mantha back into the courtroom to read the sentence for Tuesday, March 17.

Gregory subsequently appealed the verdict to the BC Court of Appeal on the grounds that Ruttan had misdirected the jury. The court unanimously dismissed the appeal, as “no substantial wrong or miscarriage of justice” had occurred in their view.

The final decision on whether someone would live or die rested with the federal cabinet. Then-prime minister John Diefenbaker opposed capital punishment, and most death sentences were commuted to life in prison. During his second term in office, from 1958 to 62, only nine of 51 capital cases considered by cabinet resulted in execution.

Gregory was a personal friend of justice minister E Davie Fulton, who was the grandson of former BC premier and Davie Street namesake AEB Davie. Gregory, who addressed Fulton on a first-name basis in their correspondence, travelled to Ottawa with hope of obtaining clemency for his doomed client.

In a letter dated Dec 18, Gregory tells Fulton he is “trespassing” on their friendship to obtain “speedy and authentic information as to the manner of handling of clemency appeals in respect of persons convicted of murder.”

“This I assure you is not prompted by idle curiosity on my part but by the fact that a client of mine yesterday was sentenced to be hanged on March 17th,” Gregory wrote on legislative letterhead.

Many others, including Perry, submitted requests for clemency. “I pray Leo’s sentence which is automatic will be commuted,” wrote Perry, who described both Jenkins and Mantha as good men. “His death per se would be no value to society. Even the tribal laws of Moses (Leviticus 24:20) were changing by the time of Jesus (St Matthew 6:38 and 39).”

He concluded that any judgment inflicted by society on Mantha would not affect Jenkins, who was “with God.”

Cabinet refused to commute his sentence.

“His brittle and explosive personality was caused in part by his early home life and his homosexual problem,” notes from the cabinet meeting read. “From the evidence it would appear that the crime was motivated by Mantha’s anger at the decision of the victim to break off their relationship.”

After some discussion, cabinet agreed with solicitor general Léon Balcer’s recommendation that “the law be allowed to take its course.”

***

Piontek says Mantha’s trial and execution triggered a “witch hunt” against homosexuals in the military.

“They were doing witch hunts before this trial for gay people,” he notes. “They’d switch them out because they found they were gay; they drummed them out just like that. But something spectacular happened — a murder — so they did more of a witch hunt. They probably drummed out quite a few people about that.”

In their 2010 book The Canadian War on Queers: National Security as Sexual Regulation, Gary Kinsman and Patrizia Gentile write that RCMP officers were sent to Victoria from Ottawa to assist in the investigation. Using Jenkins’s address book to find names of suspected gay men, naval security and the RCMP interrogated and purged or transferred men who were gay or presumed to be gay.

Piontek says he was given the “bum’s rush” out of the Navy and spent his last day in a cell.

“The shore patrol came for me and threw me in a cell,” he says. “You’d have to go and get the linen and someone in the shore patrol would escort you and you’d get your tray of food … And the next morning, they took all my stuff back, signed me out and goodbye.”

Most of the people involved in the case have since died, but many key players, including the lawyers on both sides, as well as the judge who issued the death sentence, publicly admitted in the years after the trial that Mantha’s sexual orientation had been a deciding factor in his fate.

In 1996, Saturday Night magazine published an article commemorating the life and achievements of Ruttan, who died that year. “Decades later, Ruttan said he believed many other scoundrels deserved death far more than Mantha,” Lynne Olver wrote. “But they were not homosexuals, and their sentences were all commuted,” Ruttan reportedly said.

Pat Johnson, writing for the Vancouver Courier in 1999, spoke with Lloyd McKenzie, who was crown counsel in Mantha’s case and later became a judge. “He had a very heavy load to carry in defending himself in this case because he was homosexual,” McKenzie told Johnson. “There’s no doubt about it. That was a strong factor militating against him.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra