My lover has no microwave but she has a pasta maker. She rolls the dough between her palms in the kitchen of her San Francisco studio. She shares a bathroom with the whole floor, but she says it’s worth it to have the kitchen. She has a mini fridge, a single burner that can only be used with the windows open and a pot with a copper bottom.

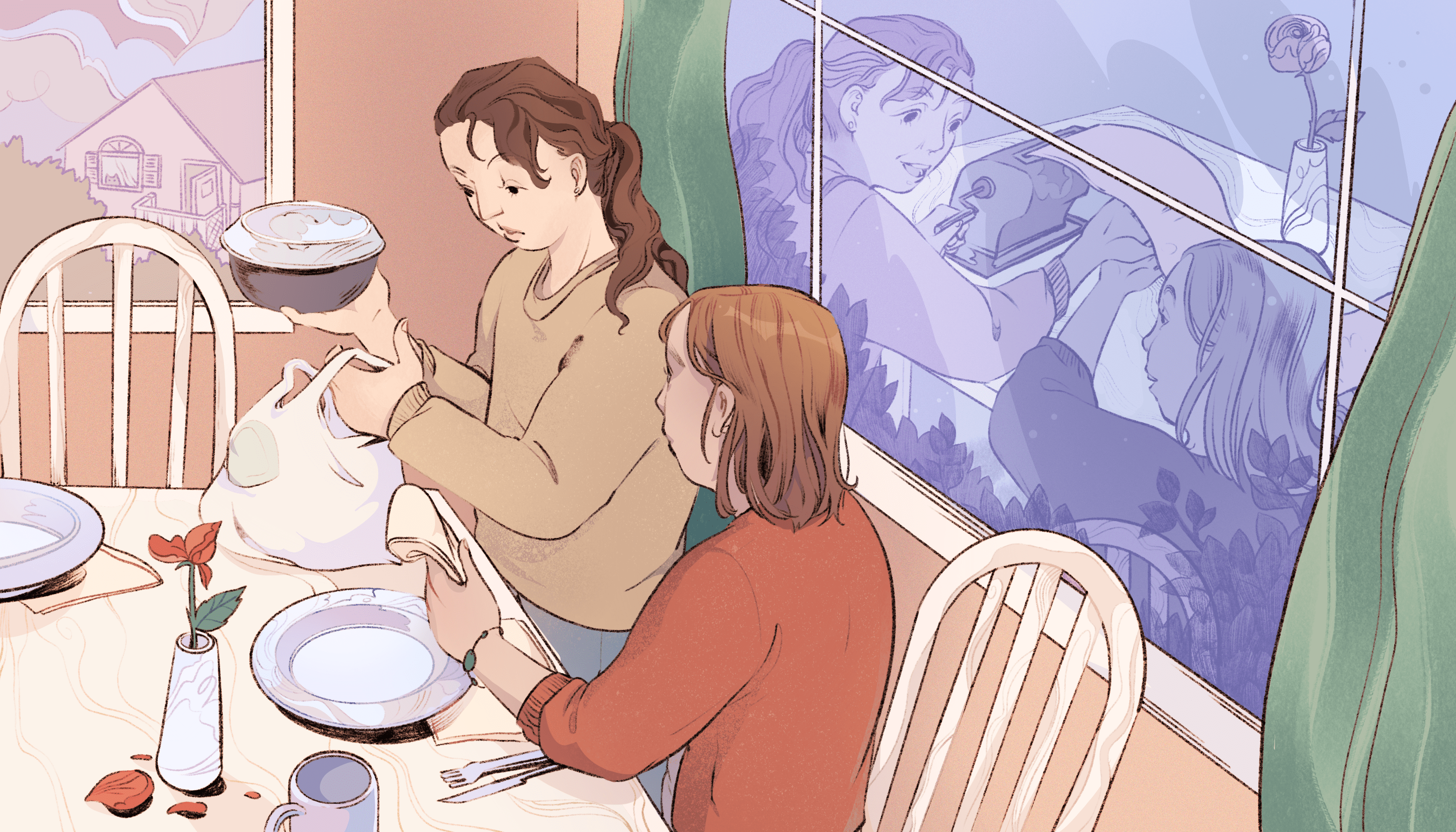

She asks to cook for me. I bring wine. Her fingers move slowly, cracking the eggs on top of the snowy flour and flicking the sunny yolks with a fork, her wrist twitching like a cat’s tail. She drags her nails against the plank of wood from an Ikea bookcase she’s set on a stool to use as counter space as she kneads and folds the dough.

Her grandmother emigrated from Hungary but lived in an Italian neighbourhood in Hartford, Connecticut; the ravioli are sacred. The steps are written on a tattered recipe card stained with olive oil and pressed fragments of basil.

“My grandmother taught me to make them so that one day I could get a nice girl to love and marry me,” she says, pricking the thin skin keeping the tomato together with the fine tip of a steak knife. “All because of the ravioli.”

We share the look, the look that says, it’s too soon to feel like this. But we are saying it in our own ways: I’m swinging my hips to the rhythm of I love you and she’s sharing her grandmother’s ravioli.

She shows her affection by being useful, showing what she can do for me, how she can love me. It’s in the crinkles around her eyes, and the thrust of her palm into the marigold lump of dough crusted in the lacy loose flour. Her patience is an art, as her hands dust and soothe the messy, all-purpose loaf that looks so fetal. It could be bread, it could be pie crust, it could be anything, but tonight it will be delicate, blooming ravioli drizzled in a butter and rosemary cream sauce.

“‘My grandmother taught me to make them so that one day I could get a nice girl to love and marry me,’ she says. ‘All because of the ravioli.’”

She cuts portions of dough and flattens them with the heel of her hand, rolling her palms over top of them so her love line and lifeline are preserved. She runs the flattened slabs through the metal slats of her pasta maker, whipping the hand crank around and around until a long, gossamer swath of ravioli crepe lays on the wooden plank. She uses a spoon to brighten the filling and artfully stuff the dough, pressed so thin it’s like a pane of stained glass. It’s late now, the process slow for inexperienced cooks, so we’ll eat at midnight.

The pasta maker is a splurge purchase, but the cutting wheel is her grandmother’s and it whistles as it cuts through the stuffed, serpentine dough, catching the beat of the water boiling on the single burner. The open window pouring in the sound of the city. The cutter leaves scalloped, sapphic edges, pressing together the two layers of thin pasta like lips puckering or hands touching. The water babbles and coos, and she pours salt into the pot like a Greek maiden pours wine into a gaping chalice.

“We share the look, the look that says, it’s too soon to feel like this.”

The upstairs neighbour is vacuuming, banging into walls and furniture. I open the wine. It’s a red that costs more than 10 dollars, which is a stretch for me, but I, too, have something to prove. I breathe with the wine, I savour the aroma of the olive oil and the sour creaminess of the ricotta, herbs I can’t name but that remind me of a garden in a book I read as a child.

“The secret is to mix in a little bit of goat cheese to bring out the tanginess,” my lover says, taking a sip of her wine. We are huddled around that piece of Ikea particle board with large streaks of the laminate scraped off by a knife or spatula. Our heads are near touching and it’s a meal that settles in the chest as well as the stomach, pouring warmth through the frostbitten parts of your insides where stress and doubt have been allowed to reside.

We eat each other as greedily as our handiwork, trading caresses like recipes, kisses like flicks of a paring knife. Her body amazes me: The scoop of her lower back, the riverbed between her breasts, the basin of her hips, her cock a coiled root vegetable. The hearty warmth of food that keeps winter misery at bay. Her teeth are a fork pressed into my shoulders, and we try not to kick over our plates or upend the table when we fall into her bed.

We emerge, stained in sauces too intimate to write down the steps. I try to remember them as clearly as I remember the care she takes when stuffing the blossoming ravioli, the gentle lowering of a slotted spoon into the churning water, salty like the sea.

We go from spending nights wrapped in each other and the hazy intoxication of brie on day-old bread and blueberry balsamic on vanilla ice cream, to long portions of quiet and store-bought gnocchi and sauce. When she offers to order in, my heart breaks. Every time she doesn’t offer to make ravioli, I hear, “You aren’t the woman I want to keep.”

Something has arisen, a tension, a gamey-ness that spoils the meat. The winter of love has been lean, unkind. I clutch my worst traits to my breast, creating space between us as all the nutrients hit my bitterness first. She says I taste different with a look on her face that means the dish didn’t turn out right. Our love affair is no longer in season, the air too cold, the ground too hard, and I’ve started buying a wine that’s less than 10 dollars.

“Every time she doesn’t offer to make ravioli, I hear, ‘You aren’t the woman I want to keep.’”

We part without breaking up, like lesbians often do. So much of our communication is unsaid, and we just know it’s time to stop texting, to wind down, to meet quarterly for lunch and pageantry. We don’t cook anymore, but we still have wine. She meets someone, I meet someone, we talk about them too much for comfort. We are too excited for one another to be believed. She eats salads and I pretend to still be working on the perfect vegetable marinade as if olive oil could ever really be improved for boiled vegetables.

“Her kiss is sweet but flat, like the hardened clumps of aged garlic on the windowsill, or rice left on the stove too long.”

We fuck again, like flipping through a scrapbook. Six seasons have gone by and my body has forgotten hers, like ingredients in a foreign language. Was it mandorla for pine nuts? No, no it was pinoli, I think. I grope around in my memory for snatches of pleasure, but fucking her is like taking up an old passion with new inspiration and finding your wrist ill-suited to hold a paintbrush. Afterwards, I make pesto, grind herbs, butter bread, pour wine and grate hard cheese, squeezing the rind between my knuckles. My feet are planted. I am ready for what she has to say, stirring the sauce too frequently so that the basil bruises.

She will breathe sharply and say, “I have no more use for this, for you.” I am convinced. I am ready for it, this monologue of parting. But she doesn’t say anything, just sips prosecco from the only wine glass I own as I boil farfalle, my feet planted until she kisses me goodbye. I ask her to stay, but she scolds me. “Ah. Never order off the menu.”

Her kiss is sweet but flat, like the hardened clumps of aged garlic on the windowsill, or rice left on the stove too long. I drink her leftover wine, eat the pesto leaning against the sink. She has left the ravioli recipe card behind, on my pillow. The olive oil and basil stains create filigree around the ancient cursive swirls of a Hungarian grandmother’s handwriting. I try to make it myself.

It’s better than sex.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra