Jun 6 was one of those fine mornings that have been so rare this year. I finished at the pentamidine clinic, a monthly ritual I have engaged in for the last decade to ward off PCP (the pneumonia infection many people with HIV get), and found myself taking a tour through AIDS history as I headed for work.

My bicycle carried me past the Casey House AIDS hospice on Isabella, then across from Jarvis Collegiate where both the AIDS Committee Of Toronto and AIDS Action Now were founded, and on through the back entrance to Cawthra Square Park.

The AIDS memorial was under repair. Workers were changing the lights that illuminate the pillars at night. I was surprised by the sight of my friend Lee, resident activist at the AIDS Committee Of Toronto, crouching in the path, a Toronto Star photographer snapping pictures. Lee was concentrating on just the right expression for the camera, not too morose, not too cheerful.

Continuing down Church I dropped in at the health food store where it was time to stock up on exotic supplements claiming to brace up a rickety immune system. My final stop before work was the hospital pharmacy to pick up $1,900 worth of medicines for the month. My employee benefit plan will pay me back, but it’s reassuring to know that Ontario’s Trillium Drug Plan would kick in if I get laid off.

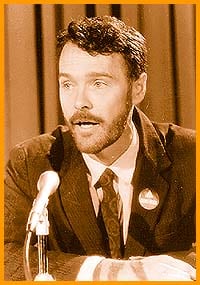

The previous week the CBC had asked me what it had been like all those years ago, how did it feel and why didn’t I die like the rest of them. On the 20th anniversary of the beginning of AIDS, activists and long term survivors like myself are briefly back in vogue.

The dark tidal wave of AIDS has swept through Toronto for 20 years, leaving more than ghosts in its wake. It has left monuments, AIDS service organizations and government programs. I had the great privilege of being part of a movement that was responsible for many of those things.

I find myself feeling ambivalent about the hoopla surrounding this anniversary. Where were all these people that they can’t remember when the waters of death began to rise? Why do they have to ask me?

On the other hand, now that the dying has been reduced to “acceptable” levels, governments have drifted back into their dreamy complacency, infection rates are rising and the pharmaceutical industry seems to spend as much on advertising as it does on research. So it’s not like there aren’t still important things to talk about, even to shout about.

So why is there so little shouting on the 20th anniversary of the beginning of AIDS?

There was a moment, earlier on in the epidemic, when we convinced ourselves that there was an HIV community. Although gay men were central, anyone who tested positive was automatically a member. Death the leveller bound us together. We shouted then, railing against “the tyranny of the uninfected,” demanding attention and access to treatment when the fight against AIDS was most often seen only in terms of preventing more infections.

Echoes of those days continue. Jim Wakeford still tilts against laws against the medical use of marijuana. The Canadian Treatment Advocates Council still nips at the heels of the pharmaceutical industry. But things are not as they were in 1988 when we burned the minister of health in effigy, or 1995 when we won the Trillium Drug Program. What happened to that HIV community?

A few months ago South African activists captured the world’s imagination when they successfully challenged the pharmaceutical industry’s obscene prices for AIDS drugs in Africa. But now some leading US activists are attacking these efforts, arguing that limiting drug company profits will result in their withdrawal from AIDS research and investment in more lucrative diseases. Are these Americans and Africans part of the same community?

HIV no longer levels us. No wonder our shouting is muted.

Such growing disparities are not the only factors. There is fatigue from 20 years of fighting. There is a feeling of futility as governments increasingly ignore people’s needs. There are the deaths of so many of our early leaders and heroes who are no longer here to offer us their experience and energies. But I think that there is an even more profound reason.

Back in 1989 a young Montreal hustler, drawn to AIDS activism by his own declining health, explained to me that AIDS was like a lens, a microscope. If we looked through it, he said, we could see all the injustices of society magnified in sharp detail.

I think AIDS activism looked through that lens and was frightened by what it saw. Can AIDS services be sustained when social services, even in the rich countries, are being cut? How can we demand housing for people with AIDS when homelessness has become common in our own city? What does the fight for care and treatment of people with AIDS mean when the public health care system is being dismantled? How can we demand AIDS research and drug access for all from a pharmaceutical industry whose goal is primarily to make money, not medicines?

Twenty years after the beginning, conquering AIDS can no longer be seen as a matter of a better drug, a new program or an expanded service. Now when we peer through the lens of AIDS we see the enormous task of challenging huge and fundamental injustices and inequalities.

I think that’s why, on a fine morning of the 20th anniversary of the beginning of AIDS, everyone seems so much more comfortable looking backward at our monuments than toward the challenges of the future.

The AIDS Committee Of Toronto is at 399 Church St, 4th floor, 416-340-2437.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra