These days, most new couples frown uncomfortably when having to tell their “how we met” story — “on an app” just doesn’t have the same ring to it. While I have no great fondness for those often retch-worthy tales (somebody runs somebody over, or spills coffee on somebody, and then they fall madly in love in the emergency room, or some such saccharine nonsense), I prefer them over the blandness of online and on-phone dating. Especially if their meet cute involves an ape and a future pope.

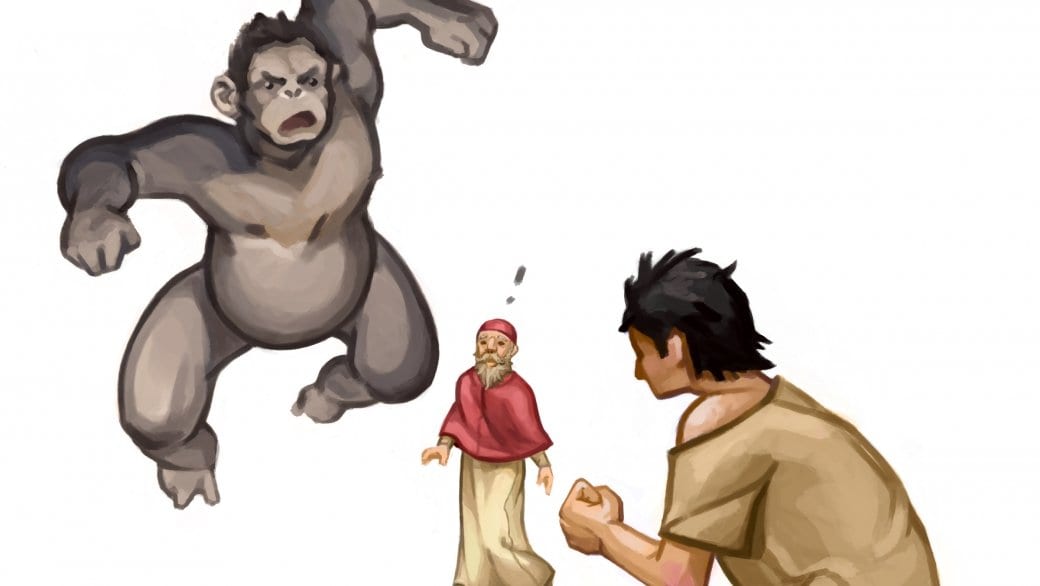

In about 1548, Giovanni Maria Ciocchi del Monte met his 15-year-old (or 16, or 17 — records are unclear) lover while the boy was fighting an ape on the dirty streets of Parma. Innocenzo, an ill-mannered beggar, was defending himself against the disgruntled pet. Del Monte’s heart was won and he quickly made the boy a cathedral provost. As a result, the boy’s nickname became “il provestino.”

When Pope Paul III died, the two main candidates to replace him — one supported by France, the other by the Holy Roman Emperor — were deadlocked. The conclave dragged on tediously and endlessly. Del Monte, an influential man who had served as governor of Rome and cardinal-bishop of Palestrina (helping to open the Counter Reformation Council of Trent in 1545), was elected as a compromise in 1550. He became Pope Julius III.

So began, as Louis Crompton writes in his essay on the now-defunct glbtq.com, “one of the most notorious homosexual scandals in the history of the papacy.” (I rely heavily on the redoubtable Crompton’s essay, and on his impressive 2003 book Homosexuality and Civilization for facts pertaining to Julius’s life and his relationship with Innocenzo.)

Julius decided the only place for his little Innocenzo was by his side. He arranged for his brother to adopt the teenage boy and, against the advice of various church leaders, he appointed his newly-minted nephew to two positions for which the boy was totally unqualified: “chief diplomatic and political agent” and cardinal (making nephews into cardinals — cardinal-nephews, as they were called — was a common practice, and is actually the source of the word “nepotism.”)

In spite of his earlier work with the Counter Reformation, Julius was a pope who liked to party. He loved feasting, the theatre and hunting — he was a pleasure-seeking pope, much like the Renaissance popes who preceded him. His personal life seems to have been no exception. According to a Venetian ambassador, he slept in not only the same bedroom, but the same bed, as his cardinal-nephew.

Roman satirical writers had a heyday, describing Innocenzo as Julius’s “Ganymede,” a reference to the hero from Greek mythology. Ganymede, whom Homer describes as the most beautiful mortal, is kidnapped by Zeus to be a cup-bearer on Olympus. Greek society used the myth as a model for pederasty, a socially acceptable sort of sexual relationship between a man and a boy. Poet Joachim du Bellay, in his series Les regrets (1558), calls Innocenzo “a Ganymede wearing the red hat on his head.”

Protestants lapped this stuff up, too. For more than 100 years, long after Julius and Innocenzo’s deaths, they used the story of this odd, famous pair in arguments against the papacy. Crompton gives a sense of some of what was said, such as that, while waiting for Innocenzo to arrive in Rome and take up his post as cardinal, Julius showed “the impatience of a lover awaiting a mistress.” They also said Julius bragged of the boy’s “prowess in bed.”

Julius was pope for only five years, dying in 1555. But the 20-something Innocenzo, who was now rich and influential, hung around for a while longer, now with the nickname “Cardinal-Monkey.” He was a thorn in the sides of succeeding popes, who did their best to keep the wild young man under control. He was banished repeatedly for such crimes as murder and rape. By the time he died, in 1577, his influence had ebbed to practically nothing.

His body lies near that of his uncle and lover, Julius, in the del Monte family chapel in the church of San Pietro in Montorio, Rome.

(History Boys appears on Daily Xtra on the first and third Tuesday of every month. You can also follow them on Facebook.)

(Original illustration by Yigi Chang.)

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra