“I have heard a queer thing said about you, Leaina,” says Clonarion, a man in love with the sacred prostitute in Lucian’s Dialogues of the Courtesans. “People say Megilla, the wealthy lady from Lesbos, is in love with you, as if she were a man, and that she — I can’t explain how . . . but . . . I have heard it said that the two of you couple up just like . . . ”

Leaina falls into an embarrassed silence and Clonarion is able to read between the lines. “What’s the matter? You are blushing. Is it true then?”

“It is true, Clonarion,” she responds. “I am ashamed. It is so strange . . . ”

“By the great Adrasteia, you must tell me about it!” her lover cries out. “What does that woman require of you? Exactly what do you do when you get into bed together?”

Lucian, a second-century Athenian writer from Samosata (Samsat in modern day Turkey), part of the Roman Empire, was a prolific satirist. For example, his A True Story is considered the earliest example of science fiction, and lampoons storytelling traditions that cite mythological stories as being true historical sources. Courtesans is smaller in scope, but no less hilarious or biting in his critique of societal norms. Courtesans is a series of vignettes, conversations between prostitutes, or with their clients, family or lovers.

Even to modern viewing, the stories seem like dirty little fables about love, jealousy and the political game of Greek hetaerae, a professional tradition of high-class, even venerated prostitutes. “At that time, pagan temples throughout the eastern Mediterranean had sacred prostitutes, and patronizing them was considered a sanctified act,” explains the Dialogues’ forward. “The hetaerae actually had a lot more freedom than other women in Greek society, particularly the sequestered wives.”

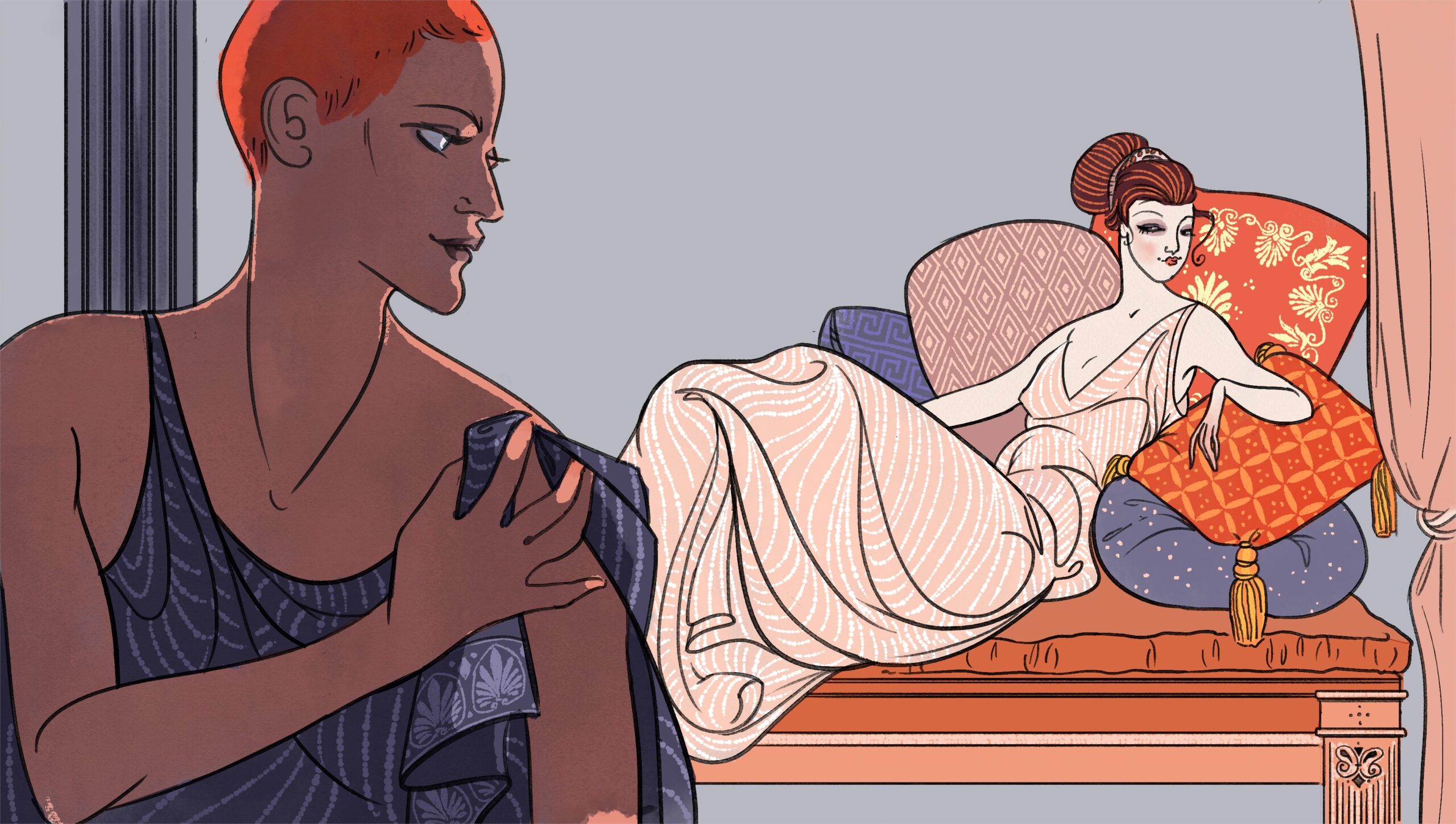

Translated and privately printed by a person identified only as ALH, “The Lesbians,” was reproduced in 1928 and features one of three formerly censored portions of Courtesans, complete with gorgeous art deco illustrations. In this section, Leaina’s lover Clonarion pleads with her to describe her foray into lesbianism with Megilla, the wealthy lady of Lesbos. The prostitute describes how the Lesbian appeared to her with Demonassa, a Corinthian, and removed her wig to show off her head, “smooth-shaven as that of a young athlete.” Leaina continues, explaining:

“I was quite scared to see this. But Megilla spoke up and said to me:

‘Tell me, O Leaina, have you ever seen a better looking young man?’

‘But I see no young man here, Megilla!’ I told her.

‘Now, now! Don’t you effeminate me!’ she reproved. ‘You must understand my name is Megillos. Demonassa is my wife.’”

Leaina is titillated, amused and confused. Is Megillos, like fabled Achilles, a man disguised as a woman, living among them? No, replies Megilla, she is not a man, a hermaphrodite, or magically transformed. “I was born with a body entirely like that of all women, but I have the tastes and desires of a man.” She’s a lesbian Lesbian.

Aside from Achilles’ crossdressing, and the myth of the Greek prophet Tiresias, which Leaina mentions as well, Lucian’s character Megilla draws on a narrative tradition of gender-bending female same-sex desire that might have influenced the story—like Zeus and Ganymede, or Apollo and Hyacinthus, these myths would be passed down through time, influencing same-sex relationships through the ages.

A contemporary story, first published only a century before Lucian’s time, Ovid’s Metamorphoses tells the story of Iphis, whose father believed a female child would be a burden, so he promised his wife he would put any female child born to death. Upon her birth, Iphis was named after her grandfather, as the name was gender-neutral. Ovid claims that this wasn’t difficult, as Iphis’ “features would have been beautiful whether they were given to a girl or a boy.”

At 13, Iphis was promised to Ianthe and presented as a boy:

“The two were equal in age, and equal in looks, and had received their first instruction, in the knowledge of life, from the same teachers. From this beginning, love had touched both their innocent hearts, and wounded them equally, but with unequal expectations. Ianthe anticipated her wedding day, and the promised marriage, believing he, whom she thought to be a man, would be her man. Iphis loved one whom she despaired of being able to have, and this itself increased her passion, a girl on fire for a girl.”

Iphis despairs that her “strange and monstrous love” will never be, but undergoes a metamorphosis through the power of the Egyptian goddess Isis, and becomes a boy.

While the tale of Iphis is ultimately heterosexually redemptive, Lucian’s Megilla appears to be a fable of perversion and titillation. Even though there’s a voyeuristic element to the story, it feels more grounded in reality than Ovid’s story of same-sex attraction, and hints at Lucian’s knowledge of lesbianism during the time of Roman Empire.

The translation’s foreword even suggests that, “Living at the height of the Roman Empire, the audience Lucian wrote for was hardly shocked by these short dialogues of the Greek hetaerae.” Clonarion acts as the audience, desperate for details about Leaina’s lesbian affair. Leaina explains:

“She pleaded so hard that I let her have her way. And you must understand that she made me a gift of a splendid necklace and several tunics of the finest linen. Then I embraced her and held her in my arms, as if she were a man. And she kissed me all over the body, and she set out to do what she had promised, panting excitedly from the great pleasure and desire that possessed her.”

“But exactly how did she manage it?” a desperately aroused Clonarion asks. “What did she do? Tell me, Leaina! Tell me especially that!”

And here’s the punchline, after describing her seduction by the lesbian Lesbian, the sacred prostitute plays coy: “Please, don’t ask me for details. These are shameful things. By the Mistress of Heaven, I will never, never, tell you that!”

While Lucian’s “The Lesbians” is clearly crafted to titillate a straight male audience, it’s interesting that between the height of the Roman Empire and the modern era there’s just so few tales of lesbianism that end happily — while Leaina ends up back in her male lover’s arms, and disparages Megilla’s attention, no one seems any worse for the exchange. While little stories pop up throughout the millennia here and there, I think of a recent screening of the 2015 film Carol where screenwriter Phyllis Nagy called Patricia Highsmith’s novel “the first lesbian story with a happy ending.” Only took us 2,000 years.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra