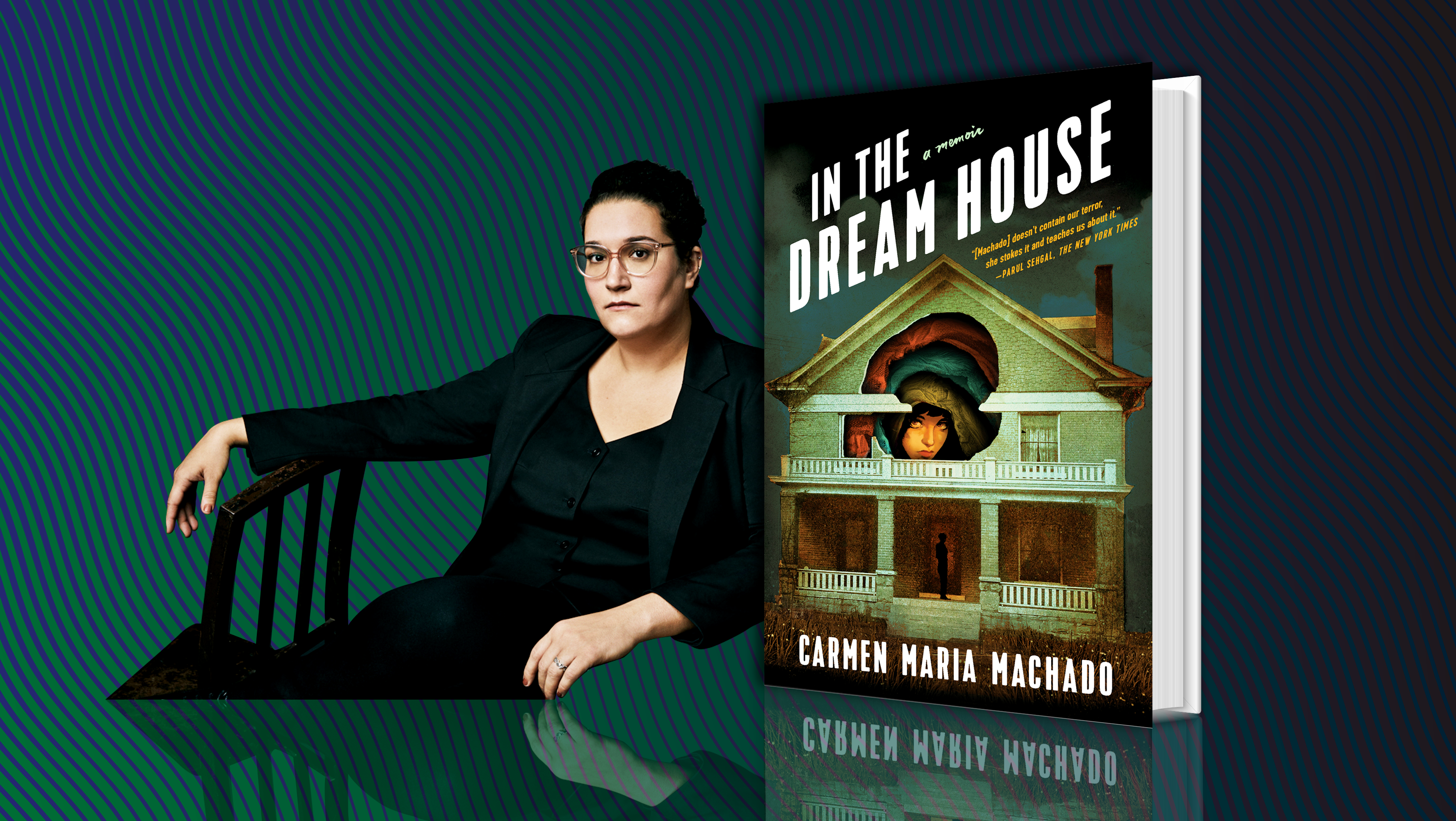

From the award-winning author of Her Body and Other Parties, Carmen Maria Machado’s new memoir is an engrossing and unflinching account of queer domestic abuse, told through a variety of innovative narratives. In this exclusive excerpt, Machado uses legal cases and queer women’s stories to analyze abuse and violence in lesbian relationships, destroying the myth of lesbian and queer women’s relationships as always safe and utopian.

In an essay in Naming the Violence—the first anthology of writing by queer women addressing domestic abuse in their community—activist Linda Geraci recalls a fellow lesbian’s paraphrasing Pat Parker to her straight acquaintance, “If you want to be my friend, you must do two things. First, forget I am a lesbian. And second, never forget I am a lesbian.”* This is the curse of the queer woman—eternal liminality. You are two things, maybe even more; and you are neither.

Heterosexuals have never known what to do with queer people, if they think of their existence at all. This has especially been the case for women—on the one hand, they seem like sinners in theory, but with no penis how do they, you know, do it? This confusion has taken many forms, including the flat-out denial that sex between women is even possible. In 1811, when faced with two Scottish schoolmistresses who were accused of being lovers, a judge named Lord Meadowbank insisted their genitals “were not so formed as to penetrate each other, and without penetration the venereal orgasm could not possibly follow.” And in 1921 the British Parliament voted against a bill that would have made illegal “acts of gross indecency between females.” Why would an early 20th-century government be so progressive? “The interpretation of this outcome offered by modern history,” writes academic Janice L. Ristock, “is that lesbianism was not only unspeakable but ‘legally unimaginable.’”

But this inability to conceive of lesbians has darker iterations too. In 1892, when Alice Mitchell slit her girl-lover Freda Ward’s throat in a carriage on a dusty Memphis street—she was enraged that Freda had, with the encouragement of her family, dissolved their relationship—the papers hardly knew what to do with themselves. In her book Sapphic Slashers, Lisa Duggan writes, “Reporters found it difficult to sketch out a clear plot or strike a consistent moral pose: Was Alice a poor, helpless victim of mental disease, or was she truly a monstrous female driven by masculine erotic and aggressive motives?…A love murder involving two girls presented an astonishing and confusing twist that confounded the gendered roles of villain and victim.”** The story was simultaneously salacious and utterly baffling. They were…engaged? Alice had given Freda a ring, along with promises of love and devotion and material support. Should they execute her for murder, or put her in a hospital for her unnatural passions? Was she a scorned lover or a madwoman? But to be a scorned lover, she’d have to be—they’d have to be—?

“I resolved to kill Freda because I loved her so much that I wanted her to die loving me,” Alice wrote in a statement her attorneys provided to the press, sounding every bit the possessive boyfriend from a Lifetime original movie. “And when she did die I know she loved me better than any human being on earth. I got my father’s razor and made up my mind to kill Freda, and now I know she is happy.”

The jury chose madwoman, and Alice spent the rest of her life in the Western State Insane Asylum in Bolivar, Tennessee.

Even when sex between women was, in its own way, acknowledged, it functioned as a kind of unmooring from gender. A lesbian acted like a man but was, still, a woman; and yet she had forfeited some essential femininity.

The conversation about domestic abuse in lesbian relationships had been active within the queer community since the early 1980s, but it wasn’t until 1989, when Annette Green shot and killed her abusive female partner in West Palm Beach after a Halloween party, that the question of whether such a thing was possible was brought before a jury and became one for the courts.

Green was one of the first queer people to use “battered woman syndrome” to justify her crime. The idea of the battered woman*** was brand new—it had been coined in the ’70s—but both abuse and the abused meant only one thing: physical violence and a white, straight woman (Green is Latina), respectively. The baffled judge eventually allowed Green’s defence, but only after insisting on renaming it “battered person syndrome,” despite the fact that both the abuser and the abused were women. Regardless, it was not successful; Green was convicted of second-degree murder. (A paralegal who worked with Green’s attorney told a reporter that “if this had been a heterosexual relationship,” she would have been acquitted.)

All of this contrasts sharply with the way narratives of abused straight (and, usually, white) women play out. When the Framingham Eight—a group of women in prison for killing their abusive partners—came into the public eye in 1992, people were similarly uncertain about what to do with Debra Reid, a Black woman and the only lesbian among them. When a panel was convened to hear the women’s stories to consider commuting their sentences, Debra’s lawyers did their best to leverage the committee’s inherent assumptions and prejudices by painting her as “the woman” in the relationship: She cooked, she cleaned, she cared for the children. The attorneys believed, rightly, that Debra needed to fit the traditional domestic abuse narrative that people understood: the abused needed to be a “feminine” figure—meek, straight, white—and the abuser a masculine one.****

That Debra was Black didn’t help her case; it worked against the stereotype. (In another early lesbian abuse case, in which a woman gave her girlfriend a pair of shiny black eyes, the prosecutor acknowledged that while she was grateful for and surprised by the abuser’s conviction, she believed that the fact that the defendant was butch and Black almost certainly played into the jury’s willingness to convict her.) The queer woman’s gender identity is tenuous and can be stripped away from her at any moment, should it suit some straight party or another. And when that happens, the results are frustratingly predictable. Most of the Framingham Eight had their sentences commuted or were otherwise released, but not Debra. (The board said that she and her girlfriend had “participated in a mutual battering relationship”—a common misconception about queer domestic violence—even though it had never come up during the hearing.) She was paroled in 1994, the second-to-last member of the group to achieve some measure of freedom. An ABC Primetime report about them barely talked to or about Debra compared to the other women. The Academy Award–winning short documentary about the Framingham

Eight—Defending Our Lives—didn’t include Debra at all.

The sort of violence that Annette and Debra experienced—brutally physical— or that Freda experienced—murder—is, obviously, far beyond what happened to me. It may seem odd, even disingenuous, to write about them in the context of my experience. It might also seem strange that so many of the domestic abuse victims that appear here are women who killed their abusers. Where, you may be asking yourself, are the abused queer women who didn’t stab or shoot their lovers? (I assure you, there are a lot of us.) But the nature of archival silence is that certain people’s narratives and their nuances are swallowed by history; we see only what pokes through because it is sufficiently salacious for the majority to pay attention.

There is also the simple yet terrible fact that the legal system does not provide protection against most kinds of abuse—verbal, emotional, psychological— and even worse, it does not provide context. It does not allow certain kinds of victims in. “By elevating physical violence over the other facets of a battered woman’s experience,” law professor Leigh Goodmark wrote in 2004, “the legal system sets the standard by which the stories of battered women are judged. If there is no [legally designated] assault, she is not a victim, regardless of how debilitating her experience has been, how complete her isolation, or how horrific the emotional abuse she has suffered. And by creating this kind of myopia about the nature of domestic violence, the legal system does battered women a grave injustice.” After all, in Gaslight, Gregory’s only actual crimes are murdering Paula’s aunt and the attempted theft of her property. The core of the film’s horror is its relentless domestic abuse, but that abuse is emotional and psychological and thus completely outside of the law.

Narratives about abuse in queer relationships—whether acutely violent or not—are tricky in this same way. Trying to find accounts, especially those that don’t culminate in extreme violence, is unbelievably difficult. Our culture does not have an investment in helping queer folks understand what their experiences mean.

When I was a teenager, there was this girl in my sophomore-year English class. She had luminous gray-green eyes and a faint smattering of freckles across her nose. She was a little swaggery and butch but also loved the same movies I did, like Moulin Rouge and Fried Green Tomatoes. We sat diagonally from each other and, every day, talked until our teacher threatened to separate us.

I liked her in a way that made me excited to go to class, but I didn’t under- stand why. She was such a good friend and so fun and so smart I wanted to rise out of my seat and grab her hand and yell, “To hell with Hemingway!” and haul her out of class; all to some end I couldn’t quite visualize. From the corner of my eye, I stared at her freckles and imagined kissing her mouth. When I thought about her, I squirmed, tormented. What did it mean?

I had a crush on her. That’s it. It wasn’t complicated. But I didn’t realize I had a crush on her. Because it was the early 2000s and I was just a baby in the suburbs without a reliable internet connection. I didn’t know any queers. I did not understand myself. I didn’t know what it meant to want to kiss another woman.

Years later, I’d figured that part out. But then, I didn’t know what it meant to be afraid of another woman.

Do you see now? Do you understand?

*Legal scholar Ruthann Robson calls this a “dual theoretical demand,” and adds, “the demand, of course, is in many cases more than dual. As Black lesbian poet Pat Parker writes in her poem For the white person who wants to know how to be my friend: ‘The first thing you do is forget that i’m Black / Second, you must never forget that i’m Black.’”

**It should be noted that Alice Mitchell was hardly the first woman to create such public confusion over her gender as it related to both her passions and her shocking act of violence.

In 1879, when Lily Duer shot her friend Ella Hearn for rejecting her love, a headline in the National Police Gazette read in part, “A Female Romeo: Her Terrible Love for a Chosen Friend of Her Own Alleged Sex [emphasis mine] Assumes a Passionate Character.” Sometime before the murder, a witness reported an exchange in which Lily said, “Ella, why will you not walk out with me? Do you not love me?” “Oh, yes, I love you,” Ella responded, “but I am afraid of you.”

***It should be noted that the word battered (as in: battered wife, battered woman, battered lesbian), while woefully imprecise and covering only a fraction of abuse experiences, was the preferred term in this era. It is, of course, a specific legal term with specific legal implications, and I have never thought of myself as a “battered” anyone. The fact that the expression persisted for so long, despite the fact that the lesbian conversation in particular focused on many kinds of abuse that were not explicitly physical, is the perfect example of how inadequate this conversation has been—discouraging useful subtlety. (Other ways in which the conversation remains inadequate: devaluing the narratives of non-white victims, insufficiently addressing non-monosexuality, rarely taking non-cisgendered people into account.)

****In a 1991 article about a white lesbian in Boise, Idaho, who successfully used “battered- wife syndrome” as a defence for killing her abusive girlfriend, the reporter emphasized that the defendant was a “diminutive 4-foot-10.” The prosecutor in the case speculated that the reason for the acquittal was that the abused wife “seemed more heterosexual,” and the abuser “more ‘lesbian.’”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra